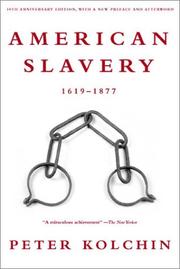

American Slavery: 1619-1877 by Peter Kolchin is a book I would recommend to all Americans. It deals with centuries of suffering by large numbers of people in a surprisingly dispassionate, almost clinical manner. One of the shameful aspects of American history, slavery deserves our attention both to correct an overly rosy view of American exceptionalism and to add insights to our understanding of the modern world.

This short book was first published in 1993, and I read the 2003 edition which includes an Afterword. I am neither a historian nor especially interested in slavery. I found the main text relatively easy to read. For those with deeper interests, the book contains many references and a detailed bibliographic essay (which I skipped).

The nature of American slavery had a geographical gradient, generally with more slaves, working under harsher conditions, in a longer lasting system the further south one went.

The book emphasizes that several agricultural systems agriculture were crucial to the development of slavery and its organization -- tobacco in the mid Atlantic, indigo and rice in the coastal south, and cotton in the deep south. These systems were export oriented, albeit some of the exports from southern colonies/states to northern colonies/states. Tobacco culture declined in the middle states as the lands became exhausted (and presumably as other sources of tobacco took European market share). Cotton culture increased and the cotton plantation system moved west from its southern roots as the American frontier moved west.

I tend to look at technology as it influences history. Thus the improvement in ship technology must have undergirded the Atlantic trade that brought slaves to the Americas and American crops to Europe. So too, the industrial revolution included the spinning and weaving technology that led to the British demand for cotton, and the complementary development of the cotton gin made the production of short staple cotton more efficient; together they made "king cotton" an export that was more valuable than all other U.S. exports by the 1850s.

For those of us interested in modern development theory, the fate of the economies that depend on export of a single, primary product such as cotton, tobacco or indigo seems familiar. It is not surprising that the plantation culture benefited the plantation owners and not the plantation workers. Kolchin makes the important point that the plantation owners faced output markets but did not face a labor market, other than the cost of purchasing slaves (a cost that went up in the 19th century after the transatlantic slave trade was halted and the value of cotton went up).

In the antebellum period, the northern states made the transition towards industrialization, with accompanying social transformations. Slavery in the North had gone out with the Independence movement, and now the North was urbanizing, creating institutions including public education. The southern states became more dominated economically by the relatively wealthy plantation owners, and there they came also to dominate state governments.

One is left wondering whether the conservatism of the South, based on the power of the haves and the powerlessness of the have-nots might be a warning to us today in the United States. Will our increasingly unequal society continue become too conservative to adapt to the technological revolution that is occurring now?

The book is good in dealing with the way in which slaves lived. It points out that early in American history bondsmen were typically European indentured servants, but that source of bonded labor was replaced by African immigrants. In the early days of African-American slavery, most of the slaves were men and both the new slaves and the new slave owners were feeling their way towards ways of dealing with each other. By the antebellum period, most African-American slaves were American born, the sex ratio had normalized, and something like family life had become more possible for the slaves.

The book has some very informative data on slave populations. It shows, for example, that in contrast to Caribbean slavery in which slaves tended to be found in large plantations with many slaves, most slaves in the United States were found in smaller holdings, often with only a few slaves. With high fertility and relatively short life expectancy, the numbers of adult slaves must have been very small in most holdings. Only in the far south did one find absentee owners of large plantations leaving their slaves in the hands of hired managers and drivers; much more often slaves were found on smaller farms in which owners not only managed the work of the slaves personally, but worked with them; slave children when young enough were allowed freedom to play and on the smaller holdings often played with the white children of their owners.

The book reflects the increasing understanding that slaves took part in the Civil War, fighting with the Union by the hundreds of thousands, working for the Union, and perhaps even more important, deserting their slave work in the Confederacy in huge numbers, thereby undermining the Confederate economy.

In the aftermath of the Civil War the South was in terrible economic shape. Now that we realize that the fall of Communism required building of new economic institutions that has taken decades and led to the rise of new powerful classes such as the Russian kleptocracy, we should not be surprised the the destruction of the Southern economic system led to a long period of economic reconstruction and saw the rise of new power centers (such as the Ku Klux Klan). The economic recovery was unfortunately complicated by a long lasting agriculture depression.

The hopes of the former slaves for a better life were only partially realized in the decades after emancipation, while the white power structure was able to re-exert economic, social and political power over the blacks. As Stephen Budiansky shows in The Bloody Shirt: Terror After Appomattox, in the deep south involuntary servitude was continued through perversion of the legal system. Not surprisingly, the latter part of the 19th century was marked by extreme disappointment with the outcome of the Civil War by the former slaves, the southern whites and the people of the north.

Perhaps the hardest thing for historians to reconstruct is the flavor of life in the past. People being people, I suppose slaves worried a lot about personal relations, their love lives, and their kids. They may have, like my Irish ancestors, taken some pleasure in the foolishness of those in power and indeed to contribute to that foolishness. There must have been huge variation among the millions of people in their multifold relationships. I, for example, suspect that Sally Hemings may have been in love with Thomas Jefferson, a very handsome man of great intelligence and ability, the most powerful man in her experience and indeed in the country, who had been widowed by her half-sister. We know that there is a lot of European ancestry in the DNA of the average black in the United States, and we must suspect that there was a lot of sex between powerful white masters and subservient black slaves, which ranged from outright rape to sexual exploitation that was tolerated because it had to be tolerated.

I would point out that there was more Indian slavery than American Slavery reports (see Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West by Ned Blackhawk). Indeed, there continue to be cases of involuntary servitude in the United States.

Author Kolchin provides considerable historiographical information. The way in which the history of slavery was written changed over time. The early histories were written from the European American perspective, while Kolchin was writing in part to summarize information that had been developed in the latter part of the 20th century with a more nuanced view of slavery, including a view that stressed the role of slaves in asserting their own interests. The Afterword is largely a discussion of the trends in the writing of the history of slavery from 1993 to 2004.

American Slavery is a reminder of how much we today owe to people who worked to build America in the past, but who did not appear in the history as studied in the schools of my youth. The African American slaves were among that number, but so were the Chinese laborers brought to build the transcontinental railway, and the poor European immigrants who provided much of the labor in the North. I recall reading that Irish immigrants were used in especially dangerous jobs in the South since slaves were too expensive to risk. Native Americans contributed to our wealth because they were dispossessed of the land and its resources without compensation.

American Slavery might well have a place on your bookshelves together with other books on American history helping to complete an overall picture of the complex social, cultural, economic and political past of the country.

No comments:

Post a Comment