I am

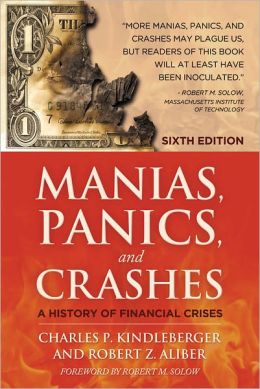

still reading

Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises by Charles P. Kindleberger and Robert Z. Aliber. I have come to the part dealing with the housing bubble of the last decade. I find that I think there is an interpretation that does not correspond exactly to the book's proposed model.

The model is based on a market with buyers and sellers much like the market provided by eBay "Buy it Now". That is buyers and sellers each can see the prices for comparable items on the market; the seller can chose a price at which to offer something; the buyer can chose an item to purchase at the offered price. The dominant elements in the process are the psychology of the buyers and sellers. (The model also involved credit; of that more later.)

There is the normal market for housing, which I think of as where almost all sellers are living in the house they are selling and almost all buyers are planning to live for a long time in the house they are buying. (In a housing bubble, many speculators are buying houses to resell and many speculators are building houses to sell.)

I have bought two houses and sold one. In all three cases, as most people in a normal housing market, I employed an agent. I needed the agent's specialized knowledge of the market as well as good advice on the transaction. As I understand it, in most such transactions there is a three percent fee on the agreed final price of the house, shared equally between the buyer's and the seller's agents. In those circumstances the agents have an incentive to achieve deals as quickly as possible, since they will then get the maximum of return per unit time worked. A $500,000 house would generate $15,000 in real estate agents' fees. If the deal can be reached in five days, that is $1,500 per agent per day; if it takes 10 days, each gets $750 per day. There is also a small advantage to both agents the higher the final price of the house. Since both the buyer and seller are probably interested in a quick sale the incentives for the buyer, seller and agents are more or less in line.

Most people buying a house will need to obtain a mortgage. Thus the buyer is involved both in finding a house and finding a mortgage. A couple of hundred years ago, banks provided the mortgage loans. If there was a small loss on a mortgage, the owners of the bank would lose money; if there were many large loss that broke the bank, the depositors would lose money as well. Thus those negotiating mortgages for banks were under pressure from both owners and depositors to make safe mortgage loans. In the latter part of the 20th century, the government guaranteed deposits, so that the risk of bad mortgage loans was then shared by the stock holders in the bank and the public.

If a potential buyer could not obtain a loan necessary to buy a house, clearly agents, potential buyer and seller all lost out. Thus it was important for the buyer's agent to find a house that the buyer could afford, and similarly, it was important that the seller's agent brought potential buyers to him who could afford the house.

The system changed in the latter part of the 20th century. Then banks came to negotiate mortgages that they sold to brokers; the brokers accepted part of the risk involved in the mortgage, but sole it on to financial institutions that bundled many similar mortgages into mortgage backed securities which they sold on to investors. The investors too assumed part of the risk inherent in the mortgage. The banks then entered into house sales transactions as agents of third parties.

In that system the incentives for all the agents are to make as many sales as possible at as high a price as possible. If a buyer purchased a house that he could not afford, or if the lender was left with a foreclosed mortgage on a property that could not be sold at sufficient price to retrieve the principle, that did not affect the profits of the real estate agents nor the bank. Agents had incentives to encourage people who could not really afford purchases to utilize sub-prime mortgages to purchase houses; they also had incentives to encourage purchases of houses at prices above their real value. Thus the incentives for the agents may have been markedly different than those of buyers and those who accepted the risk on mortgages.

The system that led to the housing bubble in the last decade reduced the risk to the bankers actually negotiating the mortgages. That led to different incentives for the the agents of the buyers, sellers and lenders. Since those agents controlled much of the information for the actual buyers and ellers in most of the housing transactions, the bubble became much more likely.

Are Cultural Differences Relevant to the Housing Market?

I recall years ago we used to visit an antique dealer in a small town in Colombia. All the houses in the village looked pretty much alike. Inside what appeared to be a very humble dwelling, however, the dealer had a rich collection of antiques for sale to discerning customers. His son had a ritzy shop in a high price district in Bogota. His was a culture in which display of affluence in one's house was not accepted.

In Haiti I recall many years ago being told that farmers sought to split their property into many widely separated small fields. The arrangement was inconvenient in terms of their work, but in the kleptocracy of the time, if their affluence was visible they would have been targeted and the ton ton macoute would have taken their property away from them.

On the other hand, Bialystock in

The Producers believes that "if you have it, flaunt it!". His was a culture that led to the MacMansion phenomenon of recent decades.

So yes, I think that culture does matter in terms of the choices people make buying their houses.

It has been suggested that in the United States people's aspirations for life style and possessions are determined by those just above them in economic status. As the top one percent got richer and richer, they bought more and more elaborate estates. The aspirations for bigger, fancier houses trickled down. Culture changed toward the MacMansion.

When Is It Good To Reduce Risk to Those Making Loans?

Hernando De Soto, in his book

The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else, suggested that giving poor people in developing countries legal rights to their land and houses would contribute to development. In many poor countries poor people actually have possession of land and houses but don't have legal title to them. These poor people can not mortgage their land or houses, can not use their real property as collateral, since the legal system does not allow lenders to take the property if a borrower fails to live up to the terms of a loan. Giving title to real property and creating a legal system that recognizes real property and mortgage responsibilities then mobilizes capital. Owners of property are empowered to borrow against it and invest the proceeds in increasing their productivity; lenders have greatly reduced risk in making loans.

Microfinance programs tend to work with community groups, depending on processes within the groups of poor people to assure that borrowers make payments and honor loan conditions. Again, the group reduces risk to lenders, mobilizing more credit for the group members.

It would seem that these approaches to reducing risk to those negotiating the loans do not lead to bubbles, while the changes in the American system that moved the risk back from the bankers to brokers and investors in mortgage backed securities did contribute to a housing bubble. Reducing risks by making borrowers more likely to pay mortgages may be useful, while reducing risk by moving it back from the bankers to more distant members of a financial change may be dangerous.