Saturday, September 27, 2014

Interesting Data on the Impact of Educational Achievement

The 2014 OECD Education at a Glance publication provides these graphs. They indicate that across nations, the more education a person has, the more trust they express in others and the more that they believe that they have a say in government. I read those data to suggest that education may tend to build social capital. (Of course, people with more education may indeed have more influence with government. They may also be of higher social status and accorded more trustworthy treatment by others.)

The data are for OECD countries, that is the "rich nations' club" nations.

Note that the impact of education on trust and feeling of having a say in government is highest for Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Netherlands, and the United States. It is low for Italy and Spain, Estonia, the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic, and Germany and Japan. It would be interesting to explore if there are aspects of the cultures of these countries that cause these results, or whether the traits are due to the nature of their historical experience.

Labels:

education

Friday, September 26, 2014

US in a converging world, Hans Rosling on CNN (Fareed Zakaria GPS)

This is several years old, but it is not outdated. The rate of economic growth of the USA and other members of the rich nation's club is limited, while less developed areas with the right conditions and policies can catch up. As Rosling shows in the video, in 1954 the United States (having emerged from World War II almost alone in the industrialized world with its industrial infrastructure intact, and indeed enhanced) had much higher per capita income than any other country. Given the large population of the USA, its GDP was huge as compared with other countries. Note too that this was a time when the European imperial powers were decolonizing. American leaders today grew up in a world in which the U.S. economy was dominant. That is no longer true today, and is likely to be even less true in the future. I think we need to face life in a world in which the European Union and China are comparable economic powers, and then India and other countries will join the club.

Labels:

Development,

Economics,

foreign policy

This should be clear enough for almost everyone

Here is the source with information on the license.

The evidence is that global warming is taking place. The processes are complex, but the scientific consensus is that global warming is taking place so fast that there will be serious consequences within 100 years. It seems clear that the cause is the release of greenhouse gases by human activity.

Labels:

Environment

Honoring the World Heritage of Information

I suggest that the most important heritage we have in the world is information. The Library of Congress has 23.6 million cataloged books. There are apparently some 12 million new and used books for sale on Amazon.com. What a huge and valuable inheritance this is from the past.

There are currently 4.6 million articles on the English language version of Wikipedia. The indexed World Wide Web contains at least 1.21 billion pages. What an inheritance of information!

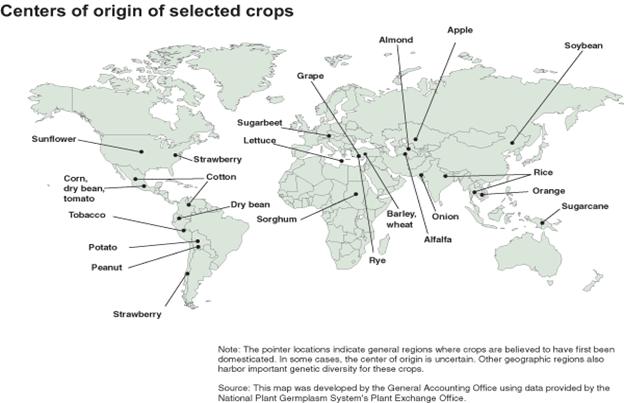

But our inherited information may be in other forms. Consider the information in domesticated plants' and animals' genomes. People have been selecting plants and animals for desired qualities for thousands of years, and breeding for such traits for decades if not centuries. The major food crops, that provide the basis of the diet for 7 billion people, have seed banks with thousand of different varieties -- each with its special properties -- in storage. Consider the many breeds of dogs and livestock, each bred for specific purposes. While we are now sequencing genomes, the information on how to create a new member of each variety or breed is present in its genes. Thus the genes of our domestic plants and animals too form a huge information heritage.

Information is present in tools and machinery. Billions of people know how to drive a car, but relatively few of them know how to repair a car, and none of them could build a car if (as in science fiction) transported back 10000 years into the past. Information was needed to process raw materials and manufacture the metals and plastics in a car; so too information was needed to design the parts of the car, and to make the machines with which the parts of the car were manufactured. We can regard all that information as embodied in the car -- the driver merely needs to know how to operate it. Indeed, how many of us would be able of find oil, get it out of the ground, and refine it into gasoline to power the car; even here we depend on exploration, drilling, pipeline, and distilling technology we as consumers don't fully understand. The roads on which the cars drive also embody a wealth of technical knowledge, as do the machines that build them, and the machines that build those machines.

Indeed, there is a huge heritage of machines -- not only those that serve consumers directly, but that are used to make the things we use every day. The development of these machines is the product of centuries of work by huge numbers of people in many places. We have inherited their legacy of knowledge and of the fruits of that knowledge -- the things themselves that indeed embody information in their very being.

Information is also institutionalized in culture. Take for example the U.S. government or the government of any large country. No one person has the knowledge and skill to perform all the jobs needed to make that government work. Indeed, no one person can even begin to describe all those jobs and their purposes. The "organization" as an institution provides the coordination, having evolved a distribution of tasks and responsibilities and institutionalized them through organizational structures and operating procedures. There are millions of institutions in modern society, each embodying information. Some, like government are formal organizations; others, such as markets, may be responsive to "hidden hands" institutionalized outside of our conscious observation.

Think of language itself. Our language includes thousands of words that represent ideas not present in the distant past -- the result of contributions of many people over a long time. Indeed, we are much more cosmopolitan, with hundreds of millions of people able to understand major international languages -- more people than existed on earth in early historical times.

And then there are the knowledge, skills, and understanding embodied in the seven billion people on earth. Some are explicit, some tacit; some have been developed by formal schooling or training, some informally. The information encoded in us behind that knowledge, skill and understanding is very different and vastly more complex than that of our ancestors 1000 or 2000 years ago. We have a huge heritage of scientific, technological, and social knowledge.

Perhaps we should honor specific world heritage. Perhaps the rice genome, or the science and technology of electricity, or the world religions are heritage more valuable and worthy of respect than the pyramids of Egypt. Perhaps the information embodied in the Library of Congress is even more deserving of honor than the Taj Mahal.

Labels:

information

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Feynman - Not Knowing Things.

Richard Feynman is thought to be a strong candidate for the smartest man since Einstein and Tesla. It is hard to disagree with him. But I think this has to be parsed.

I think he is quite right about science. People had a lot of evidence that Newton was right, but then Einstein came along with a very different formulation which made a prediction of an observation that was different than the prediction made by Newton's theory of gravity. There were several tries to make that observation, and finally it was made successfully and the data supported Einstein and not Newton. Scientists have not found a prediction from Newton's theory of gravitation that is better supported by data than an alternative prediction from Einstein's theory. Nor has anyone come up with a theory, the predictions of which are superior to those of Einstein's theory.

But scientists dearly hope that such a theory will be produced -- thus their acceptance of Einstein's theory of Relativity is not that it is "true" but only that they have been unable after many attempts to find a prediction that from the theory that is demonstrated to be false. Of course, it someone came up with such an observation, the immediate assumption would be that the observation was wrong -- that a mistake had been made in the prediction or the measurement. Only when the accuracy of the extrapolation of the theory in the prediction has been verified independently, and when the observation has been replicated independently will scientists accept the new theory as better than the one it supplants.

The alternative view is that something may be true enough for all practical purposes. I am pretty sure that when Prof. Feynman put his shoes on in the morning he did not spend a lot of time wondering if they were really where he perceived them to be, nor whether he would be successful in putting them on in the same way he had put shoes on many, many times before. Maybe someone played a practical joke during the night and those assumptions would not be true, but like all of us he would proceed on the basis that the assumptions were true enough for the practical purpose at hand.

I do love the idea that there are questions to which I will never know the answers, and indeed questions which I may never be able adequately to formulate. Maybe someone will come along in a while, perhaps a long while and find an answer or formulate a better new question.

Internet Connectivity Map

This is a cartogram, a map in which the area of each country is proportional to its online population, based on 2011 data. So countries with large land areas but small populations — like Canada and Russia — appear shrunken, while dense, well-connected areas like South Korea and Belgium appear larger than life.

The most striking region is Africa. The continent has 1.1 billion people, more than three times the population of the United States. Yet thanks to dismal internet penetration rates, the entire continent shows up as smaller than the US.The total number of Internet users today is approaching 3 billion. That is about 42% of the world population. We can leave out infants and people who can not or choose not to connect, but there are still a lot of people who are unconnected.

Labels:

ICT

Wednesday, September 24, 2014

Laws per Congress -- Truman to Obama

I quote from the source of the graph:

The 113th Congress is on track to be the “least productive” in six decades, sending President Obama fewer public bills to be signed into law than any president since the end of World War II.Too many members are too busy seeking election to the next Congress to work on the people's business now. I think the nation has a lot of problems that the government should be addressing, so I am not sure that the 113th Congress simply spinning its wheels for two years is in our interest.

John Delaney, my Congressman newly elected in the Maryland 6th District, seems to have tried valiantly to legislate in the country's interest. If you can not say the same for yours:

- Perhaps you have not been following his/her record closely, and you should check before the November election.

- Or you know that she/he has not been working for us, and you should vote accordingly.

Labels:

politics

Deaths Of Children Under Age 5, Per 1,000 Live Births

In 2013, 6.3 million children under the age of 5 died. Not as horrific as the death toll in the past, but still far too many preventable deaths!

Labels:

Development,

Health

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

UNESCO Could Better Promote Peace by Shifting its Culture Programs

|

| © UNESCO/Michel Ravasdsar |

UNESCO was created to build the defenses of peace in the minds of men. It was supposed to deal in culture (as well as education, science and communications) with that objective. I wonder if its programs on the conservation of historical sites and artifacts and its recognition of unique expressions of diverse cultures are the only or even the best way for cultural programs to increase the probability of peace.

UNESCO has focused on "culture" in the narrow sense of the arts and the interests of museums. The broader interpretation of "culture" would include the institutions of a society and the technology that it uses. Perhaps UNESCO would better focus on helping people to understand the heritage from which they currently benefit in everyday life, and the ways in which cultures are converging by adopting parts of the global heritage that solve current problems.

|

| Giza Pyramids from the Air. |

Why would we celebrate the fact that the ancient Egyptians accepted a claim of divinity and built the pyramid for a pharaoh -- and then did so again and again? Rather than celebrate the pyramids built to support such delusions millennia ago, might UNESCO not equally well celebrate the fact that our understanding of mental illness has developed greatly and is widely shared among world cultures.

Many societies today share the ability to build such a pyramid, should they so choose, and to build it bigger, better and faster than the ancient Egyptians could have done. (Indeed, many countries could then vaporize the pyramid in a single thermo-nuclear explosion – something a pharaoh might have liked.) The accumulated heritage of know how to do such construction and the fact that that cultural heritage of knowledge is widely shared might also be worthy of UNESCO's celebration, at least since that knowledge is applied towards improving people's lives.

The ancient Egyptians were wrong about what was above us in the heavens. Today we inherit centuries of accumulated astronomical knowledge. We know quite a bit about the solar system, and we have put a man on the moon and vehicles on Mars. If we choose to do so we could very quickly put a man’s ashes into orbit, or his mummy in a casket on the moon. Indeed, if we choose, we could put a colony on Mars in this century. The cultural heritage of centuries of human effort to build that understanding of man’s place in the universe is truly worthy of UNESCO’s celebration. That shared knowledge that we are so insignificant a part of the universe might even be used to encourage mankind toward peace on our fragile planet.

|

| Source |

People live longer, healthier lives than ever before in history, and we do so by the billions. This is the result in part of modern medical technology and institutions that have been developed and shared worldwide. So too, our health and longevity are the result of agriculture that benefits from crops and livestock domesticated all over the world and are now shared among cultures; farmers everywhere benefit from technology and institutional forms developed outside their own countries. So too, people live in more hygienic environments enjoying the fruits of engineering and building technology developed in many countries over centuries and now shared globally. Manufacturing provides the inputs needed by medicine, agriculture, and engineering -- again the heritage of an industrial revolution that has lasted centuries and taken place in many countries. UNESCO could celebrate the heritage shared by all nations in these modern sectors.

In its celebrations of cultural heritage, UNESCO has focused on accomplishments of the past – typically very old accomplishments of cultures shared by relatively small populations. (The population of Egypt at the time the pyramids were built was onle a couple of million.) In its focus on cultural diversity, UNESCO emphasizes aspects of a country’s tastes in food, music or drama from those of other countries. Might UNESCO also focus on cultural heritage that saves lives and helps people live healthier, more comfortable lives? Might UNESCO not also to focus on aspects of modern culture that have benefited from developments in many places at many times, and that are widely shared? Would people be as likely to go to war if they recognized more fully how much they owed to other cultures, and how similar their modern culture really is to other modern cultures?

UNESCO unlikely to promote peace by emphasizing things made in the past in cultural isolation, nor by emphasizing the differences in tastes among current cultures? Rather, UNESCO should emphasize the centuries of effort that constitute the heritage of modern societies and the continuing accumulation of new abilities that will be the heritage of future generations; UNESCO should emphasize that the sharing of useful knowledge and abilities is leading to convergence among cultures. UNESCO can help build the defenses of peace by showing how we are alike and becoming more so as we work together to create better lives for people?

The Daily Show helps John Holdren Show Up Congressional Know Nothings

After about a minute, this video gets to Congressional questioning of Presidential Science Advisor John Holdren. Three members of the House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space and Technology show their opposition to the scientific consensus that human activity is putting greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that result in global warming. Dr. Holdren shows how poorly those Congressmen understand their own arguments. Jon Stewart makes it all look funny.

It is not funny. Sea level will rise over future decades because glaciers and ice packs are melting, and because even water expands when it is heated. The oceans contain a huge amount of water, and heating it only a few degrees will increase the volume of the oceans enough to raise their surface area perceptibly. That will be bad news for coastal zones, especially when storms and hurricanes hit. That in turn will be bad news for people all over the world.

Climate change is likely to require farmers to change how they farm and foresters to respond to new threats to their forests. Global warming may expand deserts. It will threaten many species as the biospheres on which they depend are threatened.

We depend on the people who make our laws and ratify our treaties to do the right thing. If they don't have the knowledge to do so, we are in big trouble. On climate change, the scientific consensus is clear. If the legislators don't understand the science, they should be guided by scientists who do understand the evidence and who can guide the legislators. This will not happen if we elect legislators who are unaware of their own ignorance and/or are too pig headed to listen to those who know better.

Labels:

Environment,

Joke,

politics

Monday, September 22, 2014

This is a good video on how scientific consensus is challenged in the media.

This video compares the techniques once used to fight the scientific evidence that smoking is unhealthy with those now used to fight the scientific evidence that emissions of greenhouse gases are causing global warming and specific climate changes in many regions.

Of course, some people must be opposing the scientific consensus out of their beliefs that the science is wrong, but doesn't it seem likely that there is money buying the campaigns? Doesn't it seem likely that if companies and people who fund the effort to discredit science would lose money if people believe the science, that their motivation is not altruistic?

Policies should be based on prudent use of the best knowledge available, and the consensus of the scientific community based on peer reviewed research is very credible knowledge.

We can choose the cultural heritage we live by!

My niece's parents immigrated from China to the United States, choosing to assume U.S. nationality. My niece chose to adopt the cultural heritage of western medicine, became a doctor and an internist, and now practices at Mass General Hospital and teaches at Harvard Medical School.

My nephew's parents immigrated from Gujarat to the USA, also choosing to assume U.S. nationality. My nephew chose to adopt the cultural heritage of American law, graduated from law school and learned the practice of law in a series of increasingly responsible positions. He was recently nominated by President Obama to be a federal judge.

One of my oldest friends was born into a Jewish family, but chose to convert to Christianity as a young man. He went to divinity school and became a Presbyterian minister. He became a recognized expert on the liturgy of his denomination, and recently retired a much loved pastor of a large Presbyterian church.

Another of my oldest friends, also brought up Jewish, became an anti-war activist as a young man. That led him to a lifetime career as a peace activist, working primarily within the American Friends Service Committee -- an organization with a deep Quaker heritage.

I am so proud of these members of my family and friends who have chosen such wonderful heritages to adopt and master.

We may choose to adopt and master a heritage peculiar to the ethnic group to which our ancestors belonged, but we may choose from a much wider range of the heritage of all mankind.

As an American I have inherited the particularly American heritage of a country that had legal slavery for nearly a century, and Jim Crow laws long after. I have inherited my country's heritage in which Indians were moved from their ancestral lands and confined to reservations if they did not adopt a European-American way of life. I have inherited the national heritage of Chinese exclusion laws and gathering of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during World War II. I reject the heritage of racism. We may and should all choose to reject cultural heritage that does not stand up to ethical standards, but we may also choose simply not to adopt practices from our ethnic ancestors or from the nations we choose as our own. President George H. W. Bush had every right not to eat broccoli simply because he didn't want to.

Check out my recent guest shot an Antiquities NOW.

Labels:

culture

Saturday, September 20, 2014

Country versus Nation

There has been a fierce debate about whether nations are necessarily diminished by the absence of statehood, and about the thin line between honourable patriotism and xenophobic nationalism.Where do you come from? I could answer "the United States of America" or "I am an American". There is a difference. The first statement says something about the country of which I am a citizen, the second about the culture I share with others of my nationality. How is it that we choose to be part of a national culture? Did the majority of voters in Scotland choose to be "British" or did they choose to be "Scots living in Great Britain"?

"Scotland independence vote exposes the established order", Financial Times, 9/18/14

The History Book Club to which I belong recently discussed a history of Poland, during which we considered the fact that Poland, which had once been the largest country in Europe, ceased to exist as a state by the end of the 18th century; for many decades a stateless people, the Polish kept their desire for a state of their own alive. Now they have one. I recently read a memoir of the Civil War, and that book also raises the issue of the nation versus the state. (See my post on the book.) I am now reading The Long Shadow: The Legacies of the Great War in the Twentieth Century by David Reynolds; President Wilson brought the issue of statehood to ethnic nations to the peace conference ending World War I and the book deals with nations and states explicitly. It occurs to me to post on the topic of the nation state in this blog.

There seem to be two different kinds of nationalisms:

- Civic nationalism: Membership of the civic nation is considered voluntary, characterized by the "will to live together". Civic-nationalist states are often characterized by adoption of the jus soli (law of the soil) for granting citizenship in the country, deeming all persons born within the integral territory of the state citizens and members of the nation, regardless of their parents' origin.

- Ethnic nationalism: The central theme of ethnic nationalists is that "nations are defined by a shared heritage, which usually includes a common language, a common faith, and a common ethnic ancestry".

A state is an organized community living under one government. States may be sovereign. The term state is also applied to federated states that are members of a federal union, which is the sovereign state.

Nation State: A state is a political and geopolitical entity, while a nation is a cultural and ethnic one. The term "nation state" implies that the two coincide, but "nation state" formation can take place at different times in different parts of the world, and has become the dominant form of world organization.

The Evolution of the United States of America.

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union were passed in 1777 and created the United States of America as a federal union of sovereign states. Thus 13 former colonies of the British empire declared themselves to be sovereign states and confederated in a perpetual union for mutual defense, to secure their liberties and for their mutual and general welfare.

I suggest that at this time in U.S. history, the people of the states were not at all sure that they formed a single ethnic nation. They shared a history as colonies of the British Empire and a common language. They did not share a common ethnic history in that there had been colonies founded by countries other than England in North America and ethnic groups from those colonies had been incorporated into the British colonies such as ethnic Dutch in New York and ethnic French in Canada (which the Articles explicitly allowed to enter the Union). Moreover, the cultures in the different colonies had evolved over more than a century under different circumstances. They did not share the same religion; Virginia in 1777 continued to have the Anglican Church as its established religion. Moreover

Congregationalists and Anglicans who, before 1776, had received public financial support, called their state benefactors "nursing fathers" (Isaiah 49:23). After independence they urged the state governments, as "nursing fathers," to continue succoring them. Knowing that in the egalitarian, post-independence era, the public would no longer permit single denominations to monopolize state support, legislators devised "general assessment schemes." Religious taxes were laid on all citizens, each of whom was given the option of designating his share to the church of his choice. Such laws took effect in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire and were passed but not implemented in Maryland and Georgia.The Constitution was written in recognition that the government of the Confederation could not achieve its purposes, especially those of mutual defense and securing liberties of citizens, and that a more powerful central government was required. However, the ratification of the Constitution involved the agreement to amend the draft which was done in 1789. The 9th and 10th amendments secured to the people and to the states the rights that were not explicitly granted to the federal government.

I suggest that many in the United States of America prior to the Civil War continued to view it as a federation of independent states, in part because they did not see themselves as a single nation. The nullification crisis during the Jackson administration indicates that the government of South Carolina thought the state had the right to opt out of federal laws. In the secessions of 1861, seven states declared themselves Republics and then joined in the Confederated States of America, again implying that their leaders believed that their states had the rights of sovereign states. Indeed, until the Civil War the "Unites States of America" was a plural, and only after did people say "the United States is" rather than "the United States are".

The United States has been described as "a nation of immigrants". As the son of immigrant parents, I know from personal experience that immigrants are part of a "civic nation" in the sense that they have voluntarily chosen to live under the laws of the United States of America and to live together with other citizens of this country in spite of the fact that they have different backgrounds than the majority of their fellow citizens. The USA has also been termed a "melting pot" in the sense that people of many ethnic ancestries have come to share many aspects of the same culture.

“We have come to realize in modern times that the ‘melting pot’ need not mean the end of particular ethnic identities or traditions”I think Kennedy's insight is correct. My enthusiasm for Irish folk music may not be shared by my Hispanic friends, nor need I share the enthusiasm of Argentine Americans for the Tango. Yet I think the state depends on a willingness to share a respect for values such as those for liberty and democracy, and for the Constitution and laws of our state.

John F. Kennedy, A Nation of Immigrants

I also know that even though the son of immigrants, I am culturally a Yank. I have been quickly recognized as such in many countries by many different people. I remember especially an occasion on my first visit to Ireland listening to an account of a phone conversation of my aunt's. (Incidentally, her son has been mistaken for me in a black and white photo.) My aunt was asked "Who was that Yank I saw you with downtown this afternoon." My aunt answered, "That was my nephew. Why did you not come up to be introduced?" Response: "I couldn't as I was a block away." I was recognized at a distance, with my Irish aunt as an American. I stand and walk like a Yank, I talk like a Yank, and I dress like a Yank, because I am one.

I went to school in the United States of America, and schooling is a powerful means of aculturation. The friends of my age for many years were also Americans and I learned our culture from them; indeed, moving from Boston to Los Angeles in the 3rd grade, I discovered that Boston culture did not sit well with the LA kids, and I would have to acquire the LA accent and my friends tastes in clothes. I have lived through countless hours of American media. I may have had immigrant parents, I may have lived abroad for years and traveled to some 50 countries, but people still have no difficulty telling that I am a Yank/Gringo/Estadounidense.

Today I think the United States of America is indeed a nation state, in which most of its citizens are ethnic Americans, albeit many with pride in aspects of their special ethnic heritage from other peoples, and some as members of our nationality by choice.

Elsewhere

The interest in the ethnically-based nation state apparently developed largely in the 19th century. That was the time of the unification of Germany and Italy as states of people sharing a common language and cultural heritage. It also seems to have been common in the wave of revolutions that swept Europe in 1848, eventually affecting some 50 countries.

Nationalism and the nation states had a rebirth in World War I, in part as a result of Woodrow Wilson's 14 points. I find it interesting that Wilson was a southerner, born before the Civil War. (He remembered seeing Robert E. Lee as a child. His father served as a Confederate chaplain in the Civil War.) His family held slaves, and must have been affected by their emancipation. He saw the destruction of the cities in which he lived as they were conquered by Union troops, and lived in the south through the reconstruction. Were his views on the rights of conquered people to determine their own fate derived from his childhood experiences? Did he see the forced conversion of a people who conceived themselves as a separate nation into members of the nation state of the United States of America as comparable to the history of the Polish, Belgians and others whose fate he championed? Perhaps.

Of course, World War I also saw the fall of the Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman and Russian empires and the creation of a number of nation states from those empires. The situation seems similar to the earlier fall of the Spanish empire, the creation of many states from former colonies, and the search for a national identity in those states.

There seem to be many ways to assemble people into "nations" if we look at history. Thus, it appears that people who define themselves as English, Scots, Welsh, and Northern Irish also have chosen to consider themselves a British nation. The United States of America continues to mold a nation of Americans from people of many historical ethnic backgrounds. Israel saw Ashkenazi, Sephardic, Mizrahi and other smaller communities of Jews -- all originally speaking different languages and having lived in many different countries -- define themselves as Israelis and learn a common language. In the same general geographic area, Arabs living in several countries, largely sharing the same Muslim religion, but denied citizenship in Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan define themselves as Palestinians. In Mexico, the descendants of indigenous Indian tribes, Spanish colonizers, African slaves, and immigrants from many countries have been forming an ethnic Mexican people for many years. (Certainly Mexican culture is easily distinguished from that of other former Spanish colonies in the Americas such as Costa Rican or Argentinian culture.)

Perhaps China and India are more like the multi-ethnic empires of the past. Their huge populations include people of many ethnic backgrounds. Those countries strive to build a civic nationalism, and may well be on their way to their own form of ethnic nationalism. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, ethnic Russians were found in Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as well as other Republics formed from the former USSR. We are watching a historic process of sorting out of the consequences of that fact. Yugoslavia discovered that the southern Slavs did not all regard themselves as members of a single Yugoslav ethnic nation, and the country broke into smaller more ethnically individual countries.

I suppose that the difference drawn between civic nationalism and ethnic nationalism is taxonomic but that real nations have aspects of both civic and ethnic nationalism in their makeup. Perhaps it is an indication that I am a Yank, but I like the idea of a nation that is united by an allegiance to a common form of government and common laws, and by respect for common values such as democracy and liberty, that still allows and values cultural diversity. How much more interesting is a country with a variety of food cultures and music cultures? How much more effective in a globalized economy is a country with people who speak other languages and understand other cultures? In a world of constant change, is it not useful to have people with different ethnic heritages who can suggest new ways of doing things?

Of course, history suggests that nationalism can be a source of conflict. In some countries, nationalism became (and perhaps still is) so ethnocentric that it denigrates other peoples and justifies aggression and wars of conquest. How do we build the defenses of peace in the minds of men of all nations? I suspect that aggression is not a necessary attribute of nationalism, and that a healthy nationalism can be achieved without jingoism, without an aggressive stance. We shall see.

Labels:

book review,

culture,

History

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Economic Conditions Driving Political Squabbling

GDP versus Median Income in the United States

|

| Source |

So where did all the extra money go? Basically it went to the people with incomes above the median, and the people who took the biggest chunk of the increase in production were the top one percent of households, as shown in the following graph.

|

| Source |

The political implications of these figures are, surely, pretty obvious. When spending power is rising broadly, benefitting most social, geographic, and income groups, it is much easier to get rival political parties and factions to coöperate. Consensus politics can thrive, as they did in the postwar era. But when most people’s incomes are stagnating, and have been for decades, politics become darker and more fractious.

With fewer gains to go around, distributional squabbles intensify—not just among various income groups but also among different social classes and ethnic groups. (As the Census Bureau data show, income disparities are still highly correlated with race.) Meanwhile, those lucky folks at the top of the income distribution, where almost all of the incremental income has accumulated over the past couple of decades, have a big incentive to get more involved politically: to prevent the adoption of redistributive policies.

To oversimplify a bit, income stagnation paired with rising inequality is a recipe for political polarization and, under the American system of divided powers, political gridlock, which is what we have. Based on the latest Census Bureau figures, there’s no sign of that changing anytime soon.

What were the 10 greatest innovations ever

Braden Kelley, who shared this image, gave his ideas on the top 10 innovations of all time. I suppose I should leave out the use of tools and the management of fire as innovations that may have predated Homo sapiens. So lets see what I come up with:

- Agriculture / domestication of food plants

- Domestication of animals

- Clothing and shoes

- Buildings

- Pottery and glass

- Metal tools

- Markets

- Government

- Boats

- Money

Labels:

Innovation

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

While we worry about Ebola, some good news!

New UN data show that child death rates are falling faster than ever. But overall progress is still short of meeting the global target of reducing the number of deaths in children under five by two-thirds (67%) between 1990 and 2015.

Source: Levels & trends in child mortality - report 2014: goo.gl/qYIYf4

Labels:

Health

Was Convergence a Bubble that has Popped?

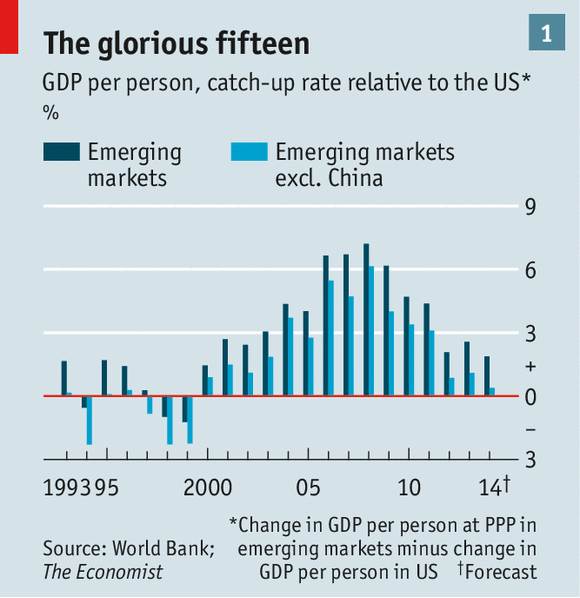

I quote from the lead article in The Economist this week (from which the graph is taken):

"When adjusted for living costs, output per person in the emerging world almost doubled between 2000 and 2009; the average annual rate of growth over that decade was 7.6%, 4.5 percentage points higher than the rate seen in rich countries.......This burst of growth struck an extraordinary blow against deprivation. The share of the developing world’s population living on less than $1.25 a day (the international definition of poverty) has fallen from 30% in 2000 to below 10%, according to an estimate by the Centre for Global Development, based on new data published by the World Bank in April.......

"Since 2008 growth rates across the emerging world have slipped back toward those in advanced economies. When the new ICP estimates are applied, the average GDP per head in the emerging world, measured on a purchasing-power-parity (PPP) basis, grew just 2.6 percentage points faster than American GDP in 2013. If China is excluded from the calculations the difference is just 1.1 percentage points."Note that the graph above is not the rate of growth of GDP per person (PPP), but rather the rate at which the GDP per capita is catching up with that of the USA. The developing countries apparently started converging economically more rapidly with the United States (and other rich countries) in 2000 and the rate of convergence increased until 2008. Since 2008, the rate of convergence has decreased year after year for developing countries with the exception of China.

Even China has a much less rapid convergence than was the case in 2008. but it continues to grow relatively rapidly. Who knows what the future will bring. "Prediction is difficult, especially about the future". One prediction is safe -- far too many people in the world will continue in extreme poverty and far too many will continue almost as poor as those in extreme poverty!

Labels:

Development,

Economics

A graph that tells the story of gun violence.

An article in The Economist discusses the rate of homicides in the United States. It points out that the murder rate in the USA is higher than that in other developed nations, nearly three times that in Canada, and that two-thirds of U.S. murders are done with guns.

"Three-quarters of all victims and nearly 90% of perpetrators are male. Black Americans are only 13% of the population, but over 50% of murder victims. Among black men between 20 and 24, the murder rate is over 100 per 100,000 (see chart)."

The data support our intuition that easy availability of guns probably increases the murder rate, and that there are social factors that influence who gets murdered. I doubt that black men want to get murdered, but they are put in danger of being murdered far more often than others in out society.

There seems to be interest in preventing violence against women, even though men are more likely to be murdered than women. But the difference in the rates of white men, white women and black women being murdered are small as compared with the huge increase in murder rate of black men.

Perhaps we should be looking more carefully at violence against black men, and seeking ways to reduce that violence.

I suspect we all know why black men are faced with so much violence. The problem is, we don't know how to quickly overcome centuries of racism directed at them.

Labels:

Other

The Civil War As Seen by a Foot Soldier in the West

|

| Source |

|

| Leander Stillwell in 1863 and later in life |

Thus Stillwell's war was spent primarily in camp, in training, and in duty guarding things critical to the war effort. Reading the book it is pretty clear that he envied the men who fought in more of the larger battles, but that he recognized that his duty was to serve wherever the army sent him at whatever duty it assigned. Most of that duty must have been pretty boring. The hopes for adventure that the 18 year old recruit set off with were pretty quickly dashed, and the man became resigned to a long hard war.

A major impression left by the book is that life in the army was really hard, even when not in battle. The food was very simple -- beans, dried peas, hardtack, salt pork and bacon seemed to provide most of the diet -- with very little fresh food other than what the solder might pick from the forest or obtain foraging while on march. Soldiers basically had to cook their own food, and until they learned how to do so, the results were not only ugly, but unhealthy. Uniforms were poorly fitted, as were shoes. A lot of the marching was apparently done thorough mud or water, and the soldiers would carry their shoes and go barefoot. There was a lot of marching, and at first the officers did not know how to give rest breaks during the long marches, The soldiers often slept in tents, sometimes what in my youth we called pup tents, and had a single blanket to sleep with; some of the cold nights of winter, when on guard duty and denied a fire, must have been very uncomfortable indeed. The sanitation in camps was often bad, and disease struck often, even after the soldiers learned to prepare their food more safely. Stillwell himself came down with malaria and later with what he called rheumatism (but which I suspect was a complication of the malaria) and was seriously ill for months -- including a bout in the field hospital.

A couple of times in the book the author talks about the motivation of the troops. He only mentions the preservation of the Union, and does not mention the ending of slavery as an institution and the emancipation of slaves; indeed, he seems to share the prejudice of the time. It seems however, that what he means by the preservation of the union is the survival of a nation with no king and no aristocracy, one where there is little discrimination by rank and where men of ability can rise in the world.

The 61st Illinois Volunteer Regiment in which Stillwell served seems from the book to have been quite egalitarian. The men had been recruited from a relatively small area of south-western Illinois, and each knew others from home. There seems to have been a relatively informal relationship between ranks, and a relatively pragmatic approach to the work at hand. Certainly Stillwell was able to rise quickly, with five promotions in 3 and 1/2 years. While the original senior officers of the regiment were selected for their political prominence, they were older and found the life very difficult, resigning eventually. Stillwell comments favorably on the West Point trained officers with prior wartime experience, on immigrants serving as officers who had served in European armies, and on officers who had risen in rank due as they learned their jobs and performed them well. He also mentions that later in life, as a judge from Kansas, he was able to fairly easily get to meet President Arthur, and to meet and spend some time with General Sherman, who what then the Chief of Staff of the Army.

I quote here a long passage from Chapter 24:

I suppose, in reminiscences of this nature, one should give his impressions, or views, in relation to that much talked about subject,—"Courage in battle." Now, in what I have to say on that head, I can speak advisedly mainly for myself only. I think that the principal thing that held me to the work was simply pride; and am of the opinion that it was the same thing with most of the common soldiers. A prominent American functionary some years ago said something about our people being "too proud to fight." With the soldiers of the Civil War it was exactly the reverse,—they were "too proud to run";—unless it was manifest that the situation was hopeless, and that for the time being nothing else could be done. And, in the latter case, when the whole line goes back, there is no personal odium attaching to any one individual; they are all in the same boat. The idea of the influence of pride is well illustrated by an old-time war story, as follows: A soldier on the firing line happened to notice a terribly affrighted rabbit running to the rear at the top of its speed. "Go it, cotton-tail!" yelled the soldier. "I'd run too if I had no more reputation to lose than you have."

It is true that in the first stages of the war the fighting qualities of American soldiers did not appear in altogether a favorable light. But at that time the fact is that the volunteer armies on both sides were not much better than mere armed mobs, and without discipline or cohesion. But those conditions didn't last long,—and there was never but one Bull Run.

Enoch Wallace was home on recruiting service some weeks in the fall of 1862, and when he rejoined the regiment he told me something my father said in a conversation that occurred between the two. They were talking about the war, battles, and topics of that sort, and in the course of their talk Enoch told me that my father said that while he hoped his boy would come through the war all right, yet he would rather "Leander should be killed dead, while standing up and fighting like a man, than that he should run, and disgrace the family." I have no thought from the nature of the conversation as told to me by Enoch that my father made this remark with any intention of its being repeated to me. It was sudden and spontaneous, and just the way the old backwoodsman felt. But I never forgot it, and it helped me several times. For, to be perfectly frank about it, and tell the plain truth, I will set it down here that, so far as I was concerned, away down in the bottom of my heart I just secretly dreaded a battle. But we were soldiers, and it was our business to fight when the time came, so the only thing to then do was to summon up our pride and resolution, and face the ordeal with all the fortitude we could command. And while I admit the existence of this feeling of dread before the fight, yet it is also true that when it was on, and one was in the thick of it, with the smell of gun-powder permeating his whole system, then a signal change comes over a man. He is seized with a furious desire to kill. There are his foes, right in plain view, give it to 'em, d—— 'em!—and for the time being he becomes almost oblivious to the sense of danger.

And while it was only human nature to dread a battle,—and I think it would be mere affectation to deny it, yet I also know that we common soldiers strongly felt that when fighting did break loose close at hand, or within the general scope of our operations, then we ought to be in it, with the others, and doing our part. That was what we were there for, and somehow a soldier didn't feel just right for fighting to be going on all round him, or in his vicinity, and he doing nothing but lying back somewhere, eating government rations.

But, all things considered, the best definition of true courage I have ever read is that given by Gen. Sherman in his Memoirs, as follows:

"I would define true courage," (he says,) "to be a perfect sensibility of the measure of danger, and a mental willingness to endure it." (Sherman's Memoirs, revised edition, Vol. 2, p. 395.) But, I will further say, in this connection, that, in my opinion, much depends, sometimes, especially at a critical moment, on the commander of the men who is right on the ground, or close at hand. This is shown by the result attained by Gen. Milroy in the incident I have previously mentioned. And, on a larger scale, the inspiring conduct of Gen. Sheridan at the battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, is probably the most striking example in modern history of what a brave and resolute leader of men can accomplish under circumstances when apparently all is lost. And, on the other hand, I think there is no doubt that the battle of Wilson's Creek, Missouri, on August 10, 1861, was a Union victory up to the time of the death of Gen. Lyon, and would have remained such if the officer who succeeded Lyon had possessed the nerve of his fallen chief. But he didn't, and so he marched our troops off the field, retreated from a beaten enemy, and hence Wilson's Creek figures in history as a Confederate victory. (See "The Lyon Campaign," by Eugene F. Ware, pp. 324-339.) I have read somewhere this saying of Bonaparte's: "An army of deer commanded by a lion is better than an army of lions commanded by a deer." While that statement is only figurative in its nature, it is, however, a strong epigrammatic expression of the fact that the commander of soldiers in battle should be, above all other things, a forcible, determined, and brave man.I liked this book very much. Indeed, I think I would have liked Leander Stillwell. He was clearly a simple man, one of considerable intelligence, much respected by his peers, who did his duty and took what came his way without complaint. In this book he writes of a few really good meals with the gusto that indicates he enjoyed them, but without complaining that they were so few in nearly four years. He writes well, and kept my interest throughout. He has a folksy humor, and frequently drew a smile. Yet he could also write about scenes of devastation, conveying the horror without excess.

I leave you sharing one of the many quotations Stillwell provided in his book:

"False as a war bulletin"

Napoleon

Labels:

book review,

History

Monday, September 15, 2014

Foreign Students in the USA

This map from a report by the Brookings Institution shows the hometowns of international students studying at U.S. schools on F-1 visas, which are the most common visas for foreign students. The size of each circle shows the number of students from that city who came to the United States to study from 2008 to 2012. The cities that sent the most students were Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, Hyderabad and Riyadh, in that order. The U.S. schools that accepted the most students were the University of Southern California, Columbia University, and the University of Illinois.Thanks to The Washington Post for this map and data.

The International Institute for Education (IIE) Open Doors report discovered 819,000 foreign students in the USA for the 2012-2013 school year. They contributed $24.7 billion to the U.S. economy. Most of the foreign students attend one of a few hundred U.S. colleges and universities, while the rest are scattered among thousands of other institutions of higher education.

Be nice to your local foreign student. These folk are likely to be the leaders of their countries in the future. If their experience in the USA is good, it will affect their view of this country for the rest of their lives. So too, if the experience is bad, it will leave a bad image for decades. The opinion of the USA that these people bring home with them will affect U.S. foreign affairs and U.S. foreign commerce in an a world growing smaller every day.

Labels:

education

Sunday, September 14, 2014

Food Is Weird: Understanding Agriculture in the Developing World

In which John Green flies in a helicopter with Bill Gates in Ethiopia, investigates a new form of cursing, and discusses agricultural reform--specifically, how the UN's World Food Program is trying to improve maize yields in Ethiopia. If you can break the vicious cycle of low incomes leading to low harvests, agricultural productivity per hectare (NOT HECTACRE) can increase dramatically, as we've seen in China and Brazil. It seems boring, I know, but this is a big reason hundreds of millions of people have emerged from poverty in the past 30 years. So hopefully it will happen in Ethiopia! But, as usual, the truth resists simplicity.This guy talks fast, and simplifies, but I think he is right about the fundamentals. Helping farmers earn more by growing more food that will reduce hunger is a very good thing to do, and it is basic to the social and economic development of poor countries. Since the poorer the country the greater the portion of its population is involved in low productivity agriculture, helping the poorest farmers to do better is a great tool to reducing extreme poverty.

One thing that the video does not mention is that it takes research and development to create the better seeds that John Green is talking about. It also involves technology to produce the fertilizer that farmers need. And there is technology needed to detect and deal with the pests and diseases that so frequently destroy crops in developing countries.

Behind every great man there is a good woman, and behind every successful farmer there is a good technology.

Labels:

Development,

Food

Saturday, September 13, 2014

The Secret Powers of Time

Renowned psychologist Professor Philip Zimbardo explains how our individual perspectives of time affect our work, health and well-being.I am not sure I agree with everything that Prof. Zimbardo says in this video, but I do believe that the perspective of time differs among cultures. I recall when I first went to work in Latin America, home of "the mañana culture," I was occasionally challenged by the difference between my sense of time and that of my friends and colleagues. The polite time to arrive for a dinner invitation was different than I expected, as was the expected start and end of a party (the only one my roommate and I threw for our neighbors lasted for three days). Sometimes things worked by the clock as I expected, and sometimes people would show up very late for an appointment and not seem to be embarrassed by having done so. On return to the USA and graduate school I wrote a paper on the phenomenon, predicting that the management of different time perspectives would be a major challenge in international organizations. So true!

I am now in my 8th decade, and I know that my perspective on time has changed with age. I now think that planning for the rest of the century makes perfect sense for many purposes. While individuals may not expect to live to see 2100, governments certainly do and businesses hope to survive that long. Planning to avoid global warming and environmental damage makes perfect sense to me.

The book mentioned in the video is A Geography Of Time: The Temporal Misadventures of a Social Psychologist by Robert V. Levine.

Friday, September 12, 2014

Population Density and Party Preference

The chart is from this article, from which I take this explanation:

The vertical axis shows a congressional district's population density (the number of people who live in each square mile).

The horizontal axis shows the district's Cook PVI score, which is really just the proclivity of the district to vote Democratic.

The pattern is clear; congressional districts with low population density (rural) are much less democratic-leaning.The same graph is shown in this article, with added information including the following graph:

(Originator of this graph)

Troy concluded that, "at about 800 people per square mile, people switch from voting primarily Republican to voting primarily Democratic." Richard Florida looked in more depth at that finding last November with a broader conversation on what this trend really says about our differing political preferences and needs in crowded cities and leafy exurbs.I looked for population data related to this idea that the population density of your Congressional District influences the voting choices and found this:

|

| Source |

|

| Source |

Thus there is a trend that may influence the redistricting after the 2020 census, and may influence the ratio of Democrats to Republicans in the Congress after 2022 or 2024. Of course, it is hard to make projections, especially about the future.

Labels:

politics,

population

The Roslings suggest we should make fact based decisions

Four heuristics that help in responding to questions about the world:

- Things are getting better, not worse.

- The world is no longer so divided between haves and have-nots; rather there is a single node distribution of income, with the poor at one tail and the rich at the other.

- Social advances are coming before income increases; the majority of people in the world are already enjoying many of the benefits we tend to associate with development.

- You overestimate the probability of harm from things you are most afraid of (and underestimate the danger of things you are accustomed to living with); you overestimate how good you are at dealing with every day dangers.

People make bad decisions every day because they don't understand reality. I like the suggestion that we don't understand global reality because of:

- Personal Bias: we grew up and live now in places that are unrepresentative.

- Outdated Facts: the things we learned in school are no longer true of today's world, nor are the things in books printed earlier than yesterday (i.e. all the books we actually read).

- News Bias: news media provide "news" that interests people rather than trying to describe the actual state of the world.

Of course no reader of this blog would fall into any of these traps (as I do all the time). But climate deniers, those who fear genetic engineering is a greater threat to the world than hunger, those who don't immunize their children because they have heard of (very rare) complications or imagined complications and others fall victim to these biases.

You are in a lot more danger in the USA from a gun owned by a good American and from a driver who considers himself safe than you are from a foreign terrorist.

Labels:

decision making,

Development,

thinking

Embrace intellectual challenges

Interesting article from Salman Khan. I quote:

Dr. Carol Dweck of Stanford University has been studying people’s mindsets towards learning for decades. She has found that most people adhere to one of two mindsets: fixed or growth. Fixed mindsets mistakenly believe that people are either smart or not, that intelligence is fixed by genes. People with growth mindsets correctly believe that capability and intelligence can be grown through effort, struggle and failure. Dweck found that those with a fixed mindset tended to focus their effort on tasks where they had a high likelihood of success and avoided tasks where they may have had to struggle, which limited their learning. People with a growth mindset, however, embraced challenges, and understood that tenacity and effort could change their learning outcomes. As you can imagine, this correlated with the latter group more actively pushing themselves and growing intellectually.It seems to me that this must be only partially right.

- People should be rewarded for choosing good things to work on. Persevering in trying to flap your arms hard enough to fly like a bird is not going to work, no matter how much you persevere. Great scientists focus on important problems that are just within their reach, and they typically learn to do so by apprenticing with an older great scientist.

- People should learn not to attempt to solve the insoluble. As a Peace Corps volunteer I saw some very good people break under the stress of trying to find a way to help the development of people who were could not progress rapidly for too many reasons. This is a corollary to the earlier idea, that you should choose good things to struggle with,

- When do you reward someone for working hard on a problem? Perhaps you should encourage people to persevere in their effort, and praise the perseverance, but perhaps the reward should be reserved for success.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

A grunt's experience in the Civil War - Part I

I have been reading Leander Stillwell's book, The Story of a Common Soldier of Army Life in the Civil War 1861-1865. Stillwell joined the Union army in January of 1862, after the first Battle of Bull Run, when President Lincoln called for volunteers for three years of service. He was 18 years old, a farm boy, on enlistment. He served the entire length of the war.

This book was written in the 20th century when he was an old man. He started the memoir as something his son could read to understand the war and his father's part in it, but later published the book. Fortunately Stillwell's family had saved the many letters he had written home as a soldier, and he had them to refer to in the writing. He also had a small diary he had kept during the latter part of the war.

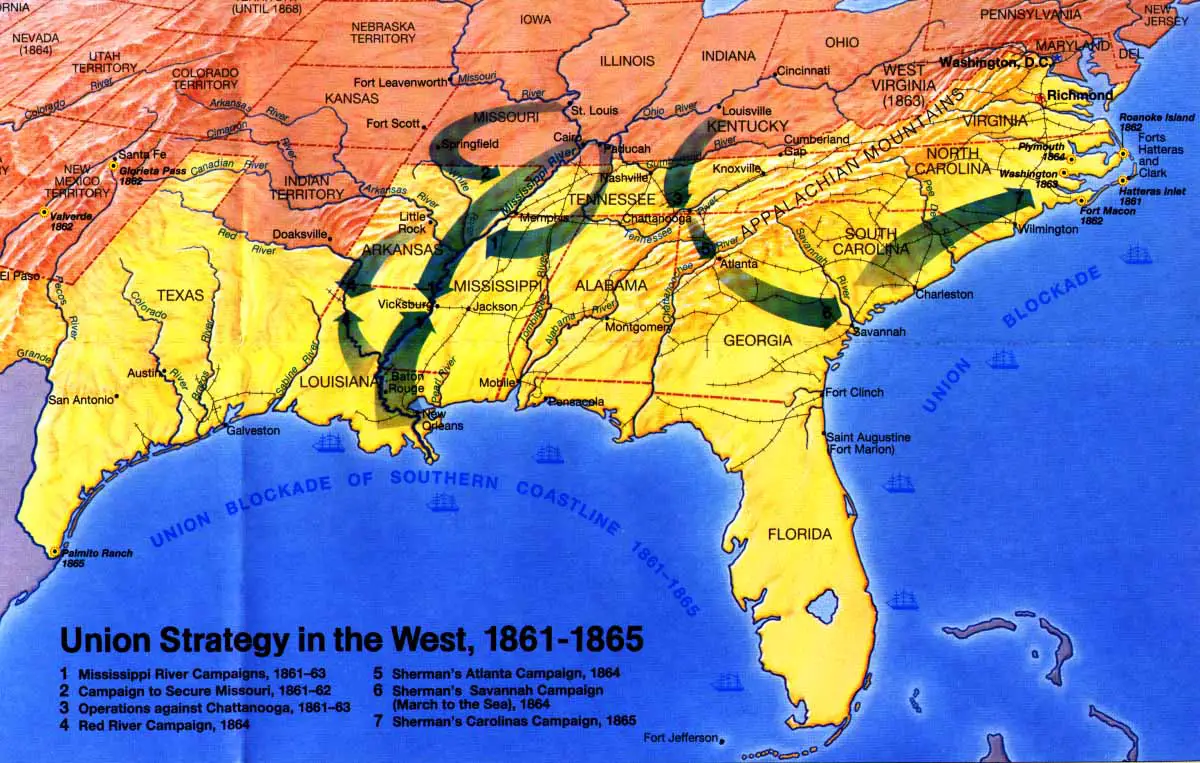

Stillwell was quickly promoted to corporal, then to sergeant and late in the war to second lieutenant; he was promoted to first lieutenant when mustering out of the army in 1865. However, he saw most of the war in the ranks rather than as an officer. He served in the Western Campaign and was present at Shiloh and Vicksburg.

I found Stillwell's biography on the Internet. After the war he went to law school, graduated, and passed the bar. He migrated to Kansas and went into private practice, but later ran for and was elected judge. He served as a judge in Kansas for many years. One can conclude that he was quite smart and quite sensible, respected by others.

He is a good writer, and in fact includes some previously published newspaper pieces that he wrote in this book. I suspect that his writing skill came from a lifetime of reading good books, his experience as a lawyer and judge, and his native intelligence.

Stillwell served in the 61st Illinois Volunteer Regiment, and I found a brief description of its service. 37 members of the regiment were killed or mortally wounded in action, and 187 died of disease. In Stillwell's war disease was a much greater danger than the enemies' bullets. This was due to the terrible sanitation of many camps leading to lots of diarrhea, and malarial mosquitoes. He also describes one camp infested with lice. There were some 800 to 900 men in the regiment at the beginning of the war. Some men left for various reasons, but apparently there were some replacements. Still the 61st was more fortunate than other units that were decimated in battle. Still the mortality in the regiment was high enough that Stillwell could call himself fortunate in surviving the war.

I have finished the first dozen chapters of the book, and wanted to share impressions while they are fresh in my mind.

We seldom see war from the point of view of the foot soldier, and this book provides a chance to do so. As a enlisted man, even as a non-commissioned officer, Stillwell understood little of the strategy of the war, or even of the tactics of battle. He went where he was ordered to go and did what he was ordered to do. There doesn't seem to have been much explaining in the process.

Perhaps one of the most significant impressions of his book is that a huge amount of his service must have been boring. In the first 12 chapters, he describes one day on the line in the battle of Shiloh and one skirmish in which his unit fired at a Confederate cavalry detachment which rather quickly retreated. Stillwells experience of the siege of Vicksburg was hearing distant artillery fire as his unit guarded a railway important for supply. The material he regards as interesting enough to describe includes the rare good meal, the sounds of unusual birds heard on night sentry duty, and drill in the operations of small and larger units (in some cases for movements never used in anger). There must have been hours, days and weeks of crashing boredom!

His home in south-western Illinois was located in a region with a large population of immigrants from slave holding states. Stillwell feels that a Democrat was chosen to form the 61st Illinois because a Democrat would be likely to better succeed in recruiting from the population that had southern sympathies and would have some Copperheads who attacked Union soldiers later in the war. He notes that few officers were available with previous military service -- some in Indian wars which was of little value in the battles of the Civil War, and some immigrants who has seen service in Europe.

He says that the men who marched off to war with him were all single. Many were boys, and the "older" men might be in their late 20s or 30s. He was eager to join the army, apparently perceiving military service as being exciting. At one point, having received a Dear John letter from a girl he liked who married a stay at home young man who clerked in a store, Stillwell expresses some disdain that man's avoiding service. At another point, Stillwell writes with admiration of an officer who encourages the troops with his own view of the importance of the purpose of the war -- the preservation of the union. It was an immigrant officer, and perhaps he had experience of the failure of the 1848 insurrections, and thus concern that the Union would remain strong enough to defend democracy. After a year in the field, and the battle of Shiloh, Stillwell writes that the boys had changed into men with serious faces.

The life of a Union soldier was hard. Food was bad (especially early in the war before the soldiers learned how to prepare it more adequately) and sometimes scarce (as when the Confederates managed to break the supply lines). While troops moved by train and steamboat for longer journeys, on railroad they traveled in box cars or flat cars, even dirtier in the latter case, and on sleeping on deck. In one case that Stillwell describes, a riverboat loaded with former paroled Confederate prisoners caught on fire, and a thousand men died, burnt to death or drowned as a result. The soldiers often slept in tents and sometimes under the sky, even in winter. They marched long distances, often in rain and mud, and early in the war commended by officers who did not understand the importance of regular rest breaks. They learned the hard way to minimize the kit that they carried with them, and lived very simply.

Stillwell describes his first battle. He was placed in a line and experienced shelling, which was almost totally ineffective. When the Confederate line appeared at their front, it quickly disappeared in the smoke generated by the black powder that was used at the time. Stillwell was looking for a target -- conditioned by years of hunting when he would never waste an expensive round of ammunition unless he was sure of a kill -- until an officer came and told him to start firing as fast as he could in the direction in which he thought there might be enemies. He describes the effort of loading and firing as fast as possible as being so demanding that he didn't think about anything else while the firing continued. (It is perhaps not surprising that so much ammunition was expended with so low a rate of men being wounder or killed in battle.) Stillwell reports that he doesn't know if his shots ever hit anyone during the war, but he supposed he must have wounded or killed.

He describes drill several times in the book, in which units of various sizes practice movements from a standard drill manual; he mentions that some of the movements practiced were never used in battle. I assume that some of the things he describes were learned in these drills, and in battle Stillwell and other soldiers could fall back on this training and do what they had reduced to a practiced skill.

I was interested that Stillwell described the behavior of someone he knew well who proved a coward in battle. The many ran to the rear at the first exchange, not to appear until the battle was over. In one battle he apparently wounded himself when he reach a safe place in the rear in order to claim the reason for his departure from the line of battle. Stillwell simply dismisses the man's behavior suggesting that he probably could not control it.

|

| Minie ball |

There is not much in the first part of the book about the transmission of information over distance by the army, perhaps because the enlisted man doesn't usually send nor receive such information. Stillwell describes the staff officer riding to his unit, no doubt carrying orders. In the siege of Vicksburg he describes signal lamps being used extensively to send coded messages between headquarters units. Although he describes guarding railroads, he has not yet mentioned guarding the telegraph lines which we know were in use.

I am looking forward to reading the rest of the book.

Labels:

book review,

History

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/1216024/InternetPopulation2011_HexCartogram_v7-01.0.png)