|

| Traditional location of Sioux tribes prior to 1770 (dark green) and their current reservations (orange) |

- Settlers, who had believed the wildly inflated tales of riches to be made by settling these lands, were deeply in debt, many near the brink of starvation.

- Lakota, who had acceded to the promises of food and technical assistance when they had been forced to give up most of their land and their traditional way of life, were even closer to starvation and even less hopeful for the future than were the settlers.

- The society of the east, which had supported millions of armed soldiers in the field during the Civil War a quarter of a century earlier, was even stronger industrially than during that war. It was deeply committed to an imperial project of settling the land from coast to coast. Its power over the settlers and Lakota was as great as that which the ancient Greeks had assumed that their gods exercised over Greek society; the power struggles between Republicans and Democrats and between those who would reform Indian policy and those who would make it even more Draconian was as difficult for people of the west to fathom as were the contests among the Greek gods to the ancient Greeks.

The result in which hundreds of Lakota were killed and wounded and scores of soldiers were also killed and wounded unfolds in retrospect like a train wreck in slow motion.

I got to thinking about this while reading Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre by Heather Cox Richardson. B&N provides a review of the book on its website. The book begins with a brief account of the events at Wounded Knee on that fateful day and comes back to those events more fully in the next to last chapter.

We find of three versions of those events:

The central thesis of Richardson's book is that the events on the Sioux Reservations that cold December must be understood in light of what had been going on in the larger society, indeed events that went back to the aftermath of the Civil War. The Republican Party had achieved great prestige as a result of the victory of the North. While today Lincoln's party is thought of as the party of abolitionists that led in the emancipation of the slaves, the Republicans also were pro industry and very much in favor of the building of railroad and telegraph infrastructure into the west. Republicans favored high levels of immigration from Europe, high tariffs to protect U.S. industry, and low rates of inflation that protected the value of the money of their rich supporters.

The Democrats came out of the war gravely weakened as a party, especially by the newly enfranchised Blacks in the south who voted Republican. As Jim Crow policies increasingly disenfranchised the Blacks, White Democrats took control of southern states and the fortunes of that party improved. So too, the many very poor immigrants of the northern cities tended to organize in support of the Democrats.

By 1890 the Republican control of the White House was in trouble. A Democrat, Grover Cleveland, had been elected in 1894, the first since the Civil War. While Benjamin Harrison (grandson of President William Henry Harrison) had been elected in 1888, Cleveland would be reelected in 1892. The Republican problems were due to the increasing disparities in wealth in the country, the perception by very large portions of the population that the government was in service of Wall Street, and the fact that the government was seen as corrupt, filling jobs as political patronage rather than for efficiency.

The railroads were especially controversial, and indeed it would be the crash of the railroad stocks that would lead to the panic of 1893 and the following recession, the worst in American history to that time. The railroad penetration of Lakota land was critical in terms of Wounded Knee. The discovery of gold in Montana had led to the creation of the Bozeman Trail cutting through lands of the Lakota, and eventually the transcontinental railroad expanded the impact on those lands. There followed the extermination of the buffalo herds on which the Lakota had come to depend. Cavalry followed to conquer the Lakota. Treaty after treaty forced the Lakota into smaller and smaller reservations -- treaties that were regularly abrogated by the federal government, ignored by settlers from the east. Indian reservations were staffed by patronage, often by incompetents, and services were provided by corrupt contractors. The railroads were also seen as offering lower rates to eastern industries sending manufactured goods into the west than to western farmers trying to sell their produce into eastern markets. They were blamed for the misleading advertising that encouraged people into settlement of western lands.

Republicans, led by Harrison, sought to find a way to retain control of the Senate and the White House. Their solution was to create a number of states out of the western territories. Those states, most of which would be reliably Republican, would elect two senators each. Since their populations of Whites (Indians were not citizens and could not vote) would be tiny, they would only elect one representative to the House each, but still there would be three members of the electoral college for the presidential election per state. The Dakota Territory was thus divided into North Dakota and South Dakota, but a huge part of western South Dakota was Sioux reservation. The solution of this latter difficulty was to take a huge portion of the reservation away from the Indians and drive them into the remaining area, offering the rest to homesteaders.

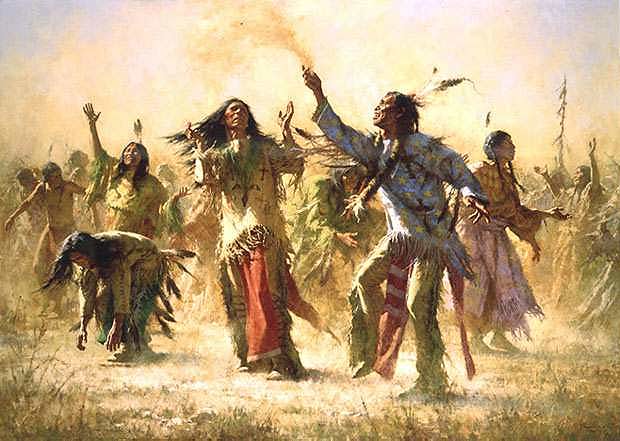

The development of the ghost dance must also be mentioned. It was a religious movement that swept the Indian territories and was taken up by many of the Lakota in their desperation. In the dances, participants often had visions which were thought to be religious inspiration; the movement was based on the belief that people would return from the afterworld restoring the buffalo herds and the environment in which the Lakota and other Indians had thrived. Whites would be swept away. The White response was disproportionate fear, leading to military action to suppress the ceremonies. Note that many of the important supporters of the Indians were Christians who sought to convert them to Christianity; were they too threatened by the cult? Clearly rather than the religious tolerance on which American society is supposed to be based, the response to the ghost dance movement was military repression. That repression was a direct cause of the Wounded Knee massacre.

Those who have not worked in the government bureaucracy may have trouble believing Richardson's depiction of the bureaucracy in the Harrison administration. When a cavalry commander in the field wished to communicate with the Indian agent in the reservation (who might have been within shouting distance), he was to send a telegram to his commanding officer. The message would be bucked up to the Secretary of War through the various layers of the War Department. The Secretary might then send it to the President or to the Secretary of the Interior, depending on the content. when it reached the Secretary of the Interior, he would pass the message to the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs who would channel it down through the layers of his Bureau until it finally reached the Indian agent. The agent would then answer reversing the long chain of communication. The process could take weeks.

Like all bureaucratic processes, the people involved had their own bureaucratic fish to fry. At the higher levels of the administration, political considerations were also likely to intrude. What a way to fight a war!

From this book, I learned of the importance of the Sherman family in American history. I knew about General William Tecumpseh Sherman, whose march to the sea was instrumental in winning the Civil War for the South and who was commanding general of the army from 1869 to 1883. I had not realized that Senator John Sherman, his brother and perhaps with an even more distinguished career, not only had his name associated with the Sherman Anti Trust legislation, but was a key member of the senate with a major responsibility for finding the financial resources with which the Union fought the Civil War. General Nelson Miles (mentioned above) was married to the niece of John and William Tecumpseh Sherman. He was later the commanding general of the United States Army.

I found Richardson's book easy to read and indeed learned a great deal from it. I was concerned by the tendency of the author to tell the reader what people thought as well as what they are recorded as having said, written or done. I doubt the accuracy of our efforts to understand the thinking of our ancestors, but I will admit that she makes the book more interesting by sharing those inferences.

Final Thoughts

There were perhaps 8 million Indians in 1492 living in what became the continental United States. The population of the continental United States today is about 310 million. The Indian culture based on hunting and gathering and simple agriculture clearly wcould not support modern levels of society. Thus something had to be done if the United States was to fulfill its "manifest destiny". Two schools of thought developed in the United States in response to this reality. One was that the Indians would have to be removed; the other was that the Indians would have to be "civilized", that is converted to live as Whites Americans and Europeans live. In fact the Lakota made huge cultural adaptations prior to the Indian Wars. They had adopted a horse culture, adopted firearms in addition to their traditional weapons, and entered into commerce first with European traders and later with those from the United States. In 1890 they were expected to make a further huge transition to farming, but were trying to do so in the face of extreme drought conditions in an area which was better suited for ranching than farming (especially since there was not yet irrigation in the region). Their plight was further exacerbated by the failure of the government to provide them with livestock, tools and technical advice, by the policies of the government to cut supplementary food supplies to the Lakota in order to force them to depend on their farm production for food, and by the corruption of the system that was in theory to supply those food supplies. There was prejudice against them and persecution by the settlers. The result was a tragedy which continues today.

We in mainstream America today live very well as a result of the injustices inflicted on the Indians in the past (and also on Blacks, Hispanics, and poor immigrants). Our mythical national history tends to ignore the racial, ethnic and religious prejudice of the past and the injustices inflicted through those prejudices. Yet I would suggest that we owe a debt to the descendants of those who for generations were not offered full participation in the American dream. Those descendants too often continue to suffer not only from the slow start available to their ancestors but to continuing prejudice.

The Lakota today are among the nation's poorest people. Here are some illuminating figures from the Pine Ridge Reservation:

We find of three versions of those events:

- There were a number of reporters on site and they filed stories describing Wounded Knee as a triumph of the U.S. cavalry over the Indians. Their version is suspect, however, since they were writing for their editors who were both trying to sell newspapers and to support their favored political parties.

- There were formal reports from the military, including the report of a formal board of inquiry and a formal report by the Department of War. These were based primarily on accounts provided by soldiers and guides who took part in the events. The initial reports are suspect because those providing the initial information were not only providing the information as they recalled it, but also had every reason to do so in such a way as to put their own actions in the best light possible. Richardson also casts doubts about the credibility of the career officers on the board of inquiry and the political actors in Washington responsible for the final content of the War Department's report. The official reports are also challenged by the views of the events from General Nelson Miles, the military commander of the region. Miles, who knew both the army and the Indians well, was not present, but he blamed the events on failed leadership of the officers in charge.

- There is the more recent interpretation of the events based largely on interviews of Lakota, cavalry scouts and people who worked on the Sioux reservations. These interviews were conducted between 1903 and 1919 (Voices of the American West, Volume 1: The Indian Interviews of Eli S. Ricker, 1903-1919 by Richard E. Jensen). This version was provided by people from their memories of events a decade or two or three in the past, whose viewpoint may also have been biased by their personal identification with participants in those events.

The central thesis of Richardson's book is that the events on the Sioux Reservations that cold December must be understood in light of what had been going on in the larger society, indeed events that went back to the aftermath of the Civil War. The Republican Party had achieved great prestige as a result of the victory of the North. While today Lincoln's party is thought of as the party of abolitionists that led in the emancipation of the slaves, the Republicans also were pro industry and very much in favor of the building of railroad and telegraph infrastructure into the west. Republicans favored high levels of immigration from Europe, high tariffs to protect U.S. industry, and low rates of inflation that protected the value of the money of their rich supporters.

The Democrats came out of the war gravely weakened as a party, especially by the newly enfranchised Blacks in the south who voted Republican. As Jim Crow policies increasingly disenfranchised the Blacks, White Democrats took control of southern states and the fortunes of that party improved. So too, the many very poor immigrants of the northern cities tended to organize in support of the Democrats.

By 1890 the Republican control of the White House was in trouble. A Democrat, Grover Cleveland, had been elected in 1894, the first since the Civil War. While Benjamin Harrison (grandson of President William Henry Harrison) had been elected in 1888, Cleveland would be reelected in 1892. The Republican problems were due to the increasing disparities in wealth in the country, the perception by very large portions of the population that the government was in service of Wall Street, and the fact that the government was seen as corrupt, filling jobs as political patronage rather than for efficiency.

The railroads were especially controversial, and indeed it would be the crash of the railroad stocks that would lead to the panic of 1893 and the following recession, the worst in American history to that time. The railroad penetration of Lakota land was critical in terms of Wounded Knee. The discovery of gold in Montana had led to the creation of the Bozeman Trail cutting through lands of the Lakota, and eventually the transcontinental railroad expanded the impact on those lands. There followed the extermination of the buffalo herds on which the Lakota had come to depend. Cavalry followed to conquer the Lakota. Treaty after treaty forced the Lakota into smaller and smaller reservations -- treaties that were regularly abrogated by the federal government, ignored by settlers from the east. Indian reservations were staffed by patronage, often by incompetents, and services were provided by corrupt contractors. The railroads were also seen as offering lower rates to eastern industries sending manufactured goods into the west than to western farmers trying to sell their produce into eastern markets. They were blamed for the misleading advertising that encouraged people into settlement of western lands.

Republicans, led by Harrison, sought to find a way to retain control of the Senate and the White House. Their solution was to create a number of states out of the western territories. Those states, most of which would be reliably Republican, would elect two senators each. Since their populations of Whites (Indians were not citizens and could not vote) would be tiny, they would only elect one representative to the House each, but still there would be three members of the electoral college for the presidential election per state. The Dakota Territory was thus divided into North Dakota and South Dakota, but a huge part of western South Dakota was Sioux reservation. The solution of this latter difficulty was to take a huge portion of the reservation away from the Indians and drive them into the remaining area, offering the rest to homesteaders.

|

| Participants in a ghost dance |

Those who have not worked in the government bureaucracy may have trouble believing Richardson's depiction of the bureaucracy in the Harrison administration. When a cavalry commander in the field wished to communicate with the Indian agent in the reservation (who might have been within shouting distance), he was to send a telegram to his commanding officer. The message would be bucked up to the Secretary of War through the various layers of the War Department. The Secretary might then send it to the President or to the Secretary of the Interior, depending on the content. when it reached the Secretary of the Interior, he would pass the message to the head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs who would channel it down through the layers of his Bureau until it finally reached the Indian agent. The agent would then answer reversing the long chain of communication. The process could take weeks.

Like all bureaucratic processes, the people involved had their own bureaucratic fish to fry. At the higher levels of the administration, political considerations were also likely to intrude. What a way to fight a war!

From this book, I learned of the importance of the Sherman family in American history. I knew about General William Tecumpseh Sherman, whose march to the sea was instrumental in winning the Civil War for the South and who was commanding general of the army from 1869 to 1883. I had not realized that Senator John Sherman, his brother and perhaps with an even more distinguished career, not only had his name associated with the Sherman Anti Trust legislation, but was a key member of the senate with a major responsibility for finding the financial resources with which the Union fought the Civil War. General Nelson Miles (mentioned above) was married to the niece of John and William Tecumpseh Sherman. He was later the commanding general of the United States Army.

I found Richardson's book easy to read and indeed learned a great deal from it. I was concerned by the tendency of the author to tell the reader what people thought as well as what they are recorded as having said, written or done. I doubt the accuracy of our efforts to understand the thinking of our ancestors, but I will admit that she makes the book more interesting by sharing those inferences.

Final Thoughts

There were perhaps 8 million Indians in 1492 living in what became the continental United States. The population of the continental United States today is about 310 million. The Indian culture based on hunting and gathering and simple agriculture clearly wcould not support modern levels of society. Thus something had to be done if the United States was to fulfill its "manifest destiny". Two schools of thought developed in the United States in response to this reality. One was that the Indians would have to be removed; the other was that the Indians would have to be "civilized", that is converted to live as Whites Americans and Europeans live. In fact the Lakota made huge cultural adaptations prior to the Indian Wars. They had adopted a horse culture, adopted firearms in addition to their traditional weapons, and entered into commerce first with European traders and later with those from the United States. In 1890 they were expected to make a further huge transition to farming, but were trying to do so in the face of extreme drought conditions in an area which was better suited for ranching than farming (especially since there was not yet irrigation in the region). Their plight was further exacerbated by the failure of the government to provide them with livestock, tools and technical advice, by the policies of the government to cut supplementary food supplies to the Lakota in order to force them to depend on their farm production for food, and by the corruption of the system that was in theory to supply those food supplies. There was prejudice against them and persecution by the settlers. The result was a tragedy which continues today.

We in mainstream America today live very well as a result of the injustices inflicted on the Indians in the past (and also on Blacks, Hispanics, and poor immigrants). Our mythical national history tends to ignore the racial, ethnic and religious prejudice of the past and the injustices inflicted through those prejudices. Yet I would suggest that we owe a debt to the descendants of those who for generations were not offered full participation in the American dream. Those descendants too often continue to suffer not only from the slow start available to their ancestors but to continuing prejudice.

The Lakota today are among the nation's poorest people. Here are some illuminating figures from the Pine Ridge Reservation:

- Recent reports vary but many point out that the median income on the Pine Ridge Reservation is approximately $2,600 to $3,500 per year.

- The unemployment rate on Pine Ridge is said to be approximately 83-85% and can be higher during the winter months when travel is difficult or often impossible.

- According to 2006 resources, about 97% of the population lives below Federal poverty levels.

- Some figures state that the life expectancy on the Reservation is 48 years old for men and 52 for women. Other reports state that the average life expectancy on the Reservation is 45 years old. These statistics are far from the 77.5 years of age life expectancy average found in the United States as a whole.

- Teenage suicide rate on the Pine Ridge Reservation is 150% higher than the U.S. national average for this age group.

- The infant mortality rate is the highest on this continent and is about 300% higher than the U.S. national average.

- School drop-out rate is over 70%.

- Teacher turnover is 800% that of the U.S. national average.

No comments:

Post a Comment