The book sketches Brazil's history from colonial days. It goes into more depth on aspects of its cultural history, such as Brazilian enthusiasm for beaches, soccer and Carnival sambas. (Rohter was a cultural reporter), The chapter on racism might be especially useful; for the casual visitor Brazilians seem racially blind, but Rohter suggests that there are aspects of racism that are important and less visible to the outsider.

Brazil is a great place to visit as a tourist, and millions will be doing so in 2014 for the World Cup soccer championship and 2016 for the summer Olympics. I still remember a trip down the Amazon as one of the great experiences of my life. A friend who visited the Pantanal told me that it was a comparably wonderful experience for a nature lover. Rio is my favorite city in the world. Sao Paulo is a huge and vibrant metropolis. Brazilia is s monument to mid 20th century modernism, and Ouro Preto is a wonderful collonial gem of a small city. If you were visiting Brazil as a tourist, this book would be a great complement to your tourist guide.

When I was a Peace Corps Volunteer in Chile in the 1960s we were told that one year 5000 PCVs had shown up in Rio for Carnival. I think you have to understand the importance of Carnival to Brazilians, and the book helps one to do so. If you want to do Carnival tourism, Rohter describes the difference in the experience in different cities and the relevant chapter is worth your attention.

I have worked as a consultant in Brazil and I would have found this book very useful as an easy to read If you have a chance to work in Brazil this would be a great source for your first entry. For example, there are a number of clues to things that a foreigner might say in innocence that might annoy Brazilian colleagues.

Much of the book focuses on the economy and those sections will be especially useful for the foreign worker. There is a good chapter on the emergence of Brazil as an agricultural export powerhouse and the emergence of Brazil's manufacturing industry.

Since Brazil's economy is primarily engaged in the production of services, it surprised me that Rohter did not devote a chapter to the problems of its service sector. Brazil's education system is a problem. There exists inadequate capacity to meet the demand for higher education. Moreover, according to a report from JPMorgan:

On average, a Brazilian student spends 6.9 years at school, which is not enough to complete the basic education. Only 22% of the population is able to complete secondary school. This is an extremely poor indicator, since in Argentina, for example, this percentage jumps to 55%. Nowadays, registration at basic education reaches 97% of students between 7 and 17 years old. This percentage decreases considerably for secondary education. Only 9% of adults complete a post-secondary (college) program.

Brazil also has a poor indicator when it comes to illiteracy rates. In 2007, 14.1 million people were illiterate. The country is behind almost all the countries in Latin America and even behind several other emerging markets.Life expectancy at birth in Brazil is ranked 74th in the world and healthy life expectancy is ranked 82nd, suggesting a deficiency in health care for a country as rich as Brazil. The transportation infrastructure is also problematic, both of lesser quality than that of other countries of comparable wealth and a problem for Brazil's economic progress.

Rohter devotes a chapter to Brazil's energy situation. This is appropriate since Brazil is apparently about to emerge as a major oil exporter. (I am under the impression that it has very substantial capacity in oil and gas, especially in deep ocean drilling.) It has very considerable hydro-power potential. It also has pioneered in biofuels, especially ethanol based on its sugarcane production. Here too Brazil pioneers in technology development.

There is a chapter on the Amazon. It is, I think, important in the minds of Brazilians and worldwide simply as a huge expanse of uncivilized country. Author Rohter shows some of the many efforts to exploit the economic resources of the Amazon. The chapter focuses on the effect of clearing the Amazon jungle on climate change, noting too the resentment of some Brazilians who feel the the global environmental community is seeking to take away from them the Amazon (and the wealth it may provide). (While the chapter on energy mentions that emissions from ethanol fueled automobiles less dangerous sources of greenhouse gases than gasoline engines, the growing of sugar cane removes carbon dioxide from the air. Brazilian sugarcane is especially useful because much of it is grown without nitrogen fertilizer, the production of which is energy intensive.) The book fails to give emphasis to the loss of biodiversity that will result from further destruction of the Amazon ecosystem or that of the Pantanal; I see that biodiversity as a global resource and its loss a potential tragedy.

Much of the book focuses on politics and government. The Portuguese monarchy is the only European monarchy to have moved its center of government to the Americas, leaving Brazil a monarchy for much of the 19th century. Rohter sketches the role of the military in the 20th century; this is contrasted with the success of the civilian governments in the last several decades. He also underlines the relatively high level of corruption in Brazilian politics and government. (He does not identify the huge pension load that has been created by government pension policies.) The book is very helpful to the outsider in explaining why Brazil's constitutional provisions for elections institutionalize the power of smaller states and dysfunctional aspects of the legislature.

The book does recognize the problem of poverty in Brazil but does not stress the problem of income distribution. According to the report from JPMorgan:

Brazil has a Gini coefficient of 0.567, which puts it among the countries with the worst wealth distribution in the world.I would have given more emphasis to the problem of Brazil's favelas, the huge slums that surround Brazil's cities and have been breeding grounds for crime and criminal organizations.

The book was first published in 2010 and the current version has a Postscript that covers the first year of Dilma's term as president of Brazil.

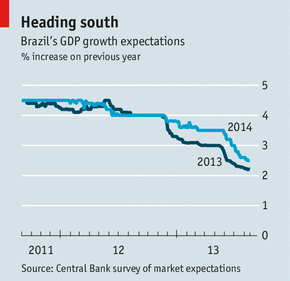

|

| Source: The Economis |

(Y)ou only need to look at the Brazilian currency, which has slumped from 1.53 reais to the dollar in mid-2011 to 2.42 reais on August 21st (2013), to realise that the gloom about Brazil persists. It has been the second worst-performing emerging-market currency this year.

Notwithstanding a relatively healthy first half, analysts’ growth projections for Brazil this year and next are plummeting (see chart).Rohter uses the example of Brazil's attraction of the World Cup and the Olympics as successes in the country's efforts to be seen as a "serious" player in international affairs. Surely there were huge public celebrations when the awards were made. More recently, however, there have been public demonstrations against the costs being incurred in preparations for the games.

Any author has to find a sweet point between telling enough to satisfy the reader and not telling the reader more than he wants to know. Rohter has found a great balance in Brazil on the Rise. While I have quibbled with some of his choices, I really liked the book and recommend it strongly.

No comments:

Post a Comment