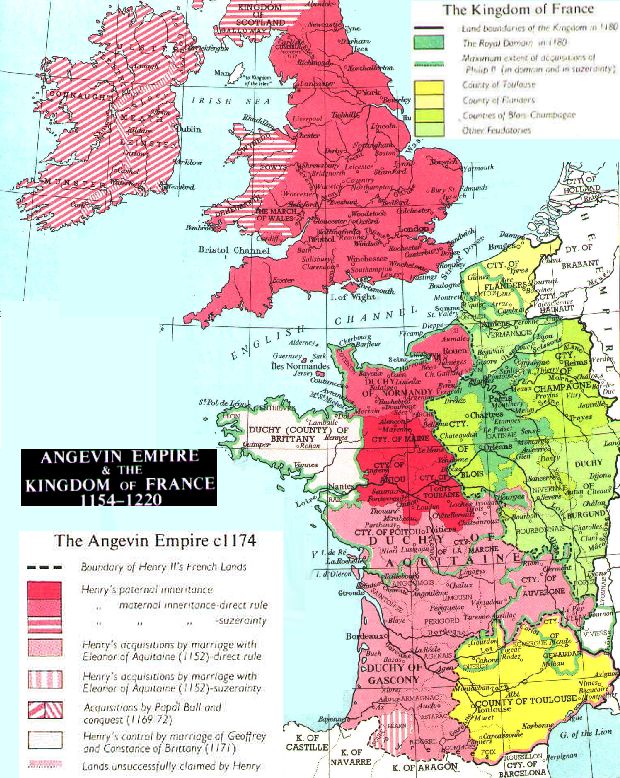

Eleanor was not only the Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right, but also Queen of France and later Queen of England. When she was queen of England she and her husband Henry II ruled the Angevin Empire stretching from Scotland to the Pyrenees. (see map.) She was born in 1122 or 1124 and lived until 1204. Thus she lived in what is termed the "High Middle Ages".

The Medieval Warm Period was from 950 to 1250. It was a time when the climate in Europe was warming. According to Wikipedia:

In the 11th century, agriculture expanded into the wilderness, in what are known as the "great clearances". During the High Middle Ages, many forests and marshes were cleared and cultivated. At the same time, during the Ostsiedlung, Germans settled east of the Elbe and Saale rivers, in regions previously only sparsely populated by Polabian Slavs. Crusaders expanded to the Crusader states, parts of the Iberian Peninsula were reconquered from the Moors, and the Normans colonized southern Italy. These movements and conquests are part of a larger pattern of population expansion and resettlement that occurred in Europe at this time.

Reasons for this expansion and colonization include an improving climate known as the Medieval warm period allowing longer and more productive growing seasons; the end of raids by Vikings, Arabs, and Magyars resulting in greater political stability; advancements in medieval technology allowing more land to be farmed; reforms of the Church in the 11th century further increasing social stability; and the rise of Feudalism, which also brought increased social stability and thus more mobility. The bonds of serfdom that tied peasants to the land began to weaken with the rise of a money economy. Land was plentiful while labor to clear and work the land was scarce; lords who owned the land found new ways to attract and keep labor. Urban centers began to emerge, able to attract serfs with the promise of freedom. As new regions were settled, both internally and externally, population naturally increased.Both England and France were feudal societies. The largely rural peasant society could support only a small urban population and a thin ruling class. There were thousands of knights (distinguished by serving as armored cavalry in war) in each country, each of whom owed fealty to an aristocrat. The aristocracy -- barons, counts, dukes, etc, -- had hierarchical structures of fealty. At the top of the heap were the kings. However, things could be complicated. Henry II in theory owed fealty to the King of France in the administration of Henry's territories in what is now France, but was Kind of England in his own right. In practice, Henry's lands were comparable in size with those that nominally owed fealty to the King of France, This would lead to the hundred years war between French and English kings (1337 to 1453).

During Eleanor's lifetime Catholicism dominated both England and France. That was true both in terms of the faith of the people and the organizational structure of the church. Eleanor herself spent several years as a participant in the Second Crusade, living for almost a year in Jerusalem. The Pope crowned kings and had power to include royals or excommunicate them. Importantly, where the royal succession depended on kings having male heirs, there was no divorce and kings depended on the church to allow annulments. Kings and the Pope uneasily shared power to appoint bishops, abbots and other officials of the church. Large numbers of people lived in monasteries and convents and these communities owned large tracts of productive lands. There were thousands of churches. The church was rich. Note that the feudal hierarchical structure also suffused the church. Priests could be married, and many lived unmarried with the mothers of their children.

Henry II was crowned king of England in 1154. That event ended the period termed "The Anarchy" -- a civil war that existed in England and Normandy from 1135 to 1153. At the end of the civil war, the

Gesta Stephani speaks of villages “standing lonely and almost empty” and of unharvested fields because the peasantry has perished or fled. Furthermore, the amount of taxes collected during the early years of Henry II reign shrank by 25% compared to 1130. This decline was not simply due to the disruption of revenue collection resulting from the civil war. Officials reported that many previously productive lands were now “waste”. Furthermore, the fiscal machinery of the English state was fully recovered by 1165, yet it was only in the very end of Henry II (1154-1189) reign when his revenues matched those enjoyed by Henry I. Thus, it is very likely that general population declined during Stephen’s reign. Rapid population expansion resumed at the end of the twelfth century and continued during most of the thirteenth century. The sudden appearance of inflation during 1180–1220 (Harvey 1973) is an indirect evidence of the changed population regime. (Source)Much of the following material comes from Secular Cycles by Peter Turchin and Sergey A. Nefedov, especially

- Chapter 3: Early Modern England: The Tudor-Stuart Cycle (1485-1730) and

- Chapter 4: Medieval France: The Capetian Cycle (1150-1450).

While population estimates from the 12th century are suspect, it seems that England had a population of 2.5 to 3.5 million. The population of France was perhaps 6 million, rising throughout the second half of the 12th century. Aquitaine was perhaps one third of France, and adding Henry II's territory

Life expectancy in medieval England was 30 years, but this was primarily due to what seems today to be very high levels of infant and child mortality. At age 21, life expectancy was another 43 years (total life expectancy of 64).

In England,

Nominal wages did not exhibit a cycle, but grew fairly monotonically. Thus, building craftsman’s wage increased from 3 in the late thirteenth century to 6 d. per day in early sixteenth century. The real wages, by contrast, exhibited an oscillation, driven by the cycling movement of prices.In France,

The early Capetian kings ruled a tiny area centered on Paris and Orléans in northern France. The situation changed dramatically during the twelfth century (when the Norman state experienced protracted civil war and change of dynasty). Under Philip II Augustus (1180-1223) the territory directly controlled by the French state expanded enormously, so that in 1223 it was ten times as large as the territory controlled by Hugh Capet. During most of the twelfth century, thus, France was at war with England under first the Norman and then the Angevin dynasties, a period of conflict sometimes called “the first Hundred Years’ War”. “Pillage, murder, banditry, and insecurity were part of everyday life”.According to Wikipedia:

A European innovation, castles originated in the 9th and 10th centuries, after the fall of the Carolingian Empire resulted in its territory being divided among individual lords and princes. These nobles built castles to control the area immediately surrounding them, and were both offensive and defensive structures; they provided a base from which raids could be launched as well as protection from enemies. Although their military origins are often emphasised in castle studies, the structures also served as centres of administration and symbols of power......

Many castles were originally built from earth and timber, but had their defenses replaced later by stone. Early castles often exploited natural defenses, and lacked features such as towers and arrowslits and relied on a central keep. In the late 12th and early 13th centuries, a scientific approach to castle defense emerged.This was the period before gunpowder arrived in Europe.

| Typical medieval farmhouse |

Housing in medieval Europe was very different depending on your social status. Pheasants usually lived in a small, wooden house with roofing made of thatch (Bunches of reeds). They indeed did have window panes but rarely had glass. The main room of these houses (which only had two rooms) had a hearth in the middle for cooking and heating of the household. The other room was where the members slept and ate. Some wealthy nobles lived in upscale castles, but most lived in manor houses. These manor homes were much more complex with paved floors and more than one story. The kitchen of the manor is equipped with large fire places to roast meats such as oxen. The kitchen is usually put in a separate building to prevent fire hazards. The homes also had tapestries hung up on the walls to add another layer of warmth during cold days. Nowadays no peasants homes from the time survive due to their poor construction, but many wealthy homes still stand today.

|

| Model of a noble's home. |

Most people in Medieval England ate bread. People preferred white bread made from wheat flour. However, only the richer farmers and lords in villages were able to grow the wheat needed to make white bread.......Rye and barley produced a dark, heavy bread. Maslin bread was made from a mixture of rye and wheat flour. After a poor harvest, when grain was in short supply, people were forced to include beans, peas and even acorns in their bread......

As well as bread, the people of Medieval England ate a great deal of pottage. This is a kind of soup-stew made from oats. People made different kinds of pottage. Sometimes they added beans and peas. On other occasions they used other vegetables such as turnips and parsnips. Leek pottage was especially popular - but the crops used depended on what a peasant had grown in the croft around the side of his home.

The peasants relied mainly on pigs for their regular supply of meat. As pigs were capable of finding their own food in summer and winter, they could be slaughtered throughout the year. Pigs ate acorns and as these were free from the woods and forests, pigs were also cheap to keep.

Peasants also ate mutton.As for drink, water was usually available only from surface sources and these were polluted an unhealthy. One reference states:

The poor drank ale, mead or cider and the rich were able to drink many different types of wines. Beer is not only one of the oldest fermenting beverages used by man, but it is also the one which was most in vogue in the Middle Ages.Another states:

Contrary to what is found all over the Internet on the subject, the most common drink was water, for the obvious reason: It's free. Medieval villages and towns were built around sources of fresh water. This could be fresh running water, a spring or, in many cases, wells.......

In larger cities, water-supply infrastructure was built to ensure public access to clean water. In medieval London, for example, the City Council began construction on what was called "the Great Conduit" in 1236......

People did drink a lot of ale and beer, but not because their water was so bad. The brews in question were much weaker than their modern equivalents but had the effect of providing much-needed calories to laborers and farmers, as well as being thirst-quenching and re-hydrating in hot weather or when working hard and losing sweat.Still another states:

In the British Isles (and) northern France......the climate was generally too harsh for the cultivation of grapes and olives. In the south, wine was the common drink for both rich and poor alike (though the commoner usually had to settle for cheap second pressing wine) while beer was the commoner's drink in the north and wine an expensive import.A significant amount of calories would have been obtained from these alcoholic beverages.

With regard to clothing, a source states:

Most people in the Middle Ages wore woolen clothing, with undergarments made of linen. Brighter colors, better materials, and a longer jacket length were usually signs of greater wealth. The clothing of the aristocracy and wealthy merchants tended to be elaborate and changed according to the dictates of fashion.......

Most of the holy orders wore long woolen habits in emulation of Roman clothing. One could tell the order by the color of the habit: the Benedictines wore black; the Cistercians, undyed wool or white. St. Benedict stated that a monk's clothes should be plain but comfortable and they were allowed to wear linen coifs to keep their heads warm. The Poor Clare Sisters, an order of Franciscan nuns, had to petition the Pope in order to be permitted to wear woolen socks.This was a very different world from ours today, a world of great poverty.

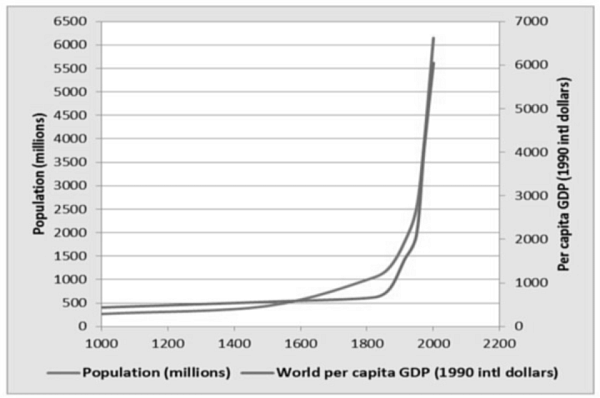

World Population and Per Capita GDP (PPP) from 1000 AD to 2001

|

| Source |

No comments:

Post a Comment