I am enjoying reading The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 by Christopher Clark, a book highly recommended by a couple of friends. The book focuses on how an assassination in 1914 resulted in the first world war. I am about half way through the book -- the portion in which Clark describes how governments came to operate by 1914.

Background

It occurs to me that the background to this book, which the author probably assumes the reader will already know, is that the first wave of globalization had been going on for some three-quarters of a century.

That globalization had been made possible by advances in technology, including railroads, steamships and the telegraph. So too, the industrial revolution had resulted in a great increase in the capacity to produce some goods (tied to the development of larger markets by the development of transportation infrastructure), and an increased demand of raw materials for the production of those goods (that could not be brought to the manufacturing hub by that transportation infrastructure).

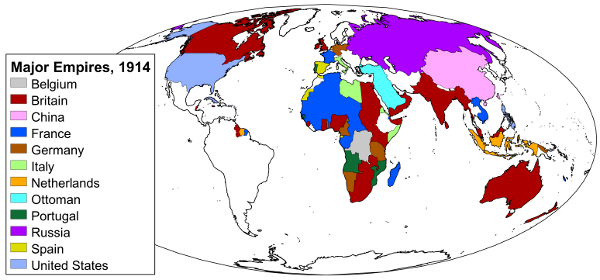

This globalization was accompanied by the the growth of empires, especially colonial empires. Thus a number of countries tried to create international trading systems via conquest of less developed areas, turning those conquered areas into colonies. The imperial country did so utilizing its advantage in guns and steel (see Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond). The industrial revolution allowed production of large amounts of cloth and clothing and other manufactured goods in the home country which could be exported to its colonies, which in turn provided food and raw material to the home country.

| ||

based on a map by Wikimedia/Andrei nacu

This Led to Complexity

The book suggests the complexity of foreign policy. Japan and Russia were competing in the east, seeking to acquire territory from China. Russia and Britain were competing in central Asia. Russia sought to acquire rights to control passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean from the Ottomans. France was willing to allow Italy to acquire Libya from the Ottomans in return for Italian support for France's acquisition of Morocco, and was willing to give Germany assurances of protection of its businesses in Morocco and land in sub-Saharan Africa for the same purpose. Russian concerns in east and central Asia limited its ability to oppose Germany. The duality between Austria and Hungary was complicated in itself, and the Austro-Hungarian empire faced the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, and Russia in the east. Britain was competing not only with Russia as described above, but with Germany and France in Africa. I could go on, but you see that these expansionist empires were rubbing up against each other all over the globe. An action in support of one country in one region of the world could have ramifications in other regions, and eventually with other countries.

Clearly if all the other empires ganged up against any one of them, that empire would be in trouble. Consequently, empires tended to form alliances. Only an alliance of empires might resist another alliance of different countries. The alliances varied over time, but the major ones in the early 20th century were the Triple Alliance (among Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy) and a network of alliances among Britain, France and Russia. France and Britain would be successful in removing Italy from its alliances with Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I.

Political Institutions

The political institutions were different in different empires. However, many were monarchies in which the monarchs shared power with an aristocratic elite. A revolution in China replaced its monarchy with a republican government in 1912. The Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman and Russian monarchies fell during or as a result of World War I. (It is tempting to believe that they were the most fragile.)

- Monarchs sometimes acted as if they actually believed that they enjoyed divine right to rule.

- Cabinets often were divided into feuding factions. Usually they were insulated from public opinion and pressure.

- Diplomats were often in opposition to their foreign ministers and prime ministers, and sometimes ambassadors would make foreign policy themselves.

- The military and the foreign policy establishments were often competing for influence and resources.

- Governments sometimes paid for press support, both within their own countries and other countries.

Policies shifted due to changes in staff, and ministers could change often, but also due to changes in the power and influence among different factions in government. When monarchs were interested in foreign policy and especially when they had strong support in the cabinet or bureaucracy, they could strongly influence policy; if the monarch then had changeable opinions or easily diverted attention, policies could change rapidly.

In these conditions it became very hard for governments to understand and predict the responses of other governments. Not only were governments opaque and their policies subject to change, but diplomatic reports could be biased. Deception was used by governments to disguise their purposes from other governments. Sometimes the foreign press was used as a divining rod to guess at the positions of foreign governments.

Author Clark's narrative leads one to be grateful that heads of government are now elected; monarchs could by totally incompetent and dangerous, but to be elected a politician has to have some competence and should be less likely to be dangerous. So too, Clark's narrative makes one glad that government policy is more open to meritocratic selection rather than restricted to aristocrats, and that bureaucracies are more professional.

Still, my experience in government suggests that many of Clark's insights about government before World War I remain remarkably relevant to current governments.

Deeper Processes

I wonder whether the 20th century was experiencing an institutional change in response to a technological change. The new technologies of the 19th and 20th century made global commerce more and more possible. If institutions could be built to support that commerce, the magic of comparative advantage would increase the benefits available to producers and consumers.

Colonialism came to be replaced by global markets. (Communism, with its central planning, was an option that many believed appropriate, but which failed in practice.) The European and other common markets have come to the fore, allowing free exchanges over large geographic areas.

Similarly, monarchies came to be replaced by more democratic political institutions -- which were more able to provide good governance. Colonial empires have disappeared, while large nation-states (China, India, the USA, Indonesia, Brazil) have survived -- perhaps due to their geographic compactness and/or their efforts to bring a national consciousness to their multi-ethnic populations. Some institutions such as the United Nations, the IMF and the World Bank (and at least 1000 other intergovernmental organizations) have been created to provide governance functions beyond those of the nation state.

Perhaps the specific events that historians so like to recount are less influential than the "economic imperative" that makes it profitable to improve economic institutions to better utilize technological advances, and that require improved political institutions to govern the economic institutions, finance the public investments needed to utilize the new technologies, and better distribute the gains. Of course, the fact that the 20th century saw a huge increase in schooling made possible by the more efficient production and distribution of goods and services also played its role in cultural development, providing support for the new technologies and political and economic institutions.

No comments:

Post a Comment