Art is a culture specific concept, and while the idea of some kinds of painting being art is widely shared in western culture, it is not shared in all cultures. While we may see ancient cave paintings in Spain and Australia as art, the people in the cultures that made those cave paintings almost certainly did not perceive them as "works of art".

Note that American concepts related to the nature of painting and art are complex. We don't see painting a wall a uniform color as art, but perhaps most often as decoration, and sometimes as building maintenance. Some kinds of painting, such as the painting of designs on pottery is probably more often seen as "craft" than as "art", although when Picasso did it people might have accorded his works the status of fine art. For some kinds of paintings, such as those of the most avant garde painters, there is disagreement as to whether they are art. The paintings of nudes on velvet are prototypical of works that some people like very much and others condemn as schlock. We recognize that the painter whose works are hot on the art market may disappear from galleries and museums in a few years, while unknown artists might eventually be recognized as masters after death (as happened with Vincent van Gogh).

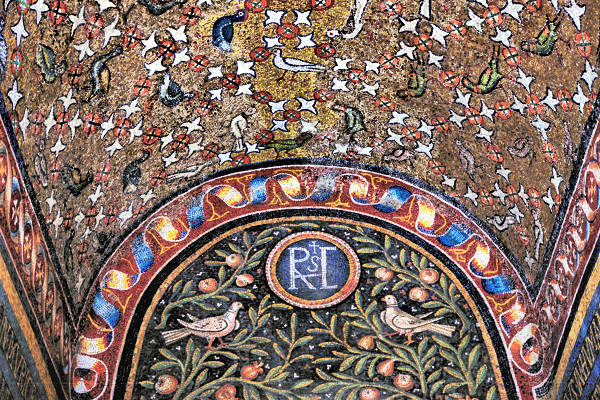

There is something strange when people from our culture apply our idea of art to paintings produced in other cultures that did not perceive those paintings as art. I suppose that much of what we now perceive as "religious art" from previous centuries was not in its own time; rather it was seen as an expression of devotion by the artists, a demonstration of affluence and power by the donor, and a means of promoting faith by religious officials. Certainly it seems that the idea of what represented a great religious painting changed over time. The icons of the medieval Orthodox church must surely have been judged by different standards than the religious paintings of the Italian Renaissance or of the Byzantine mosaics of Ravenna.

|

| Ravenna - Mosaic in the Bishop's Palace |

On the other hand, there are many cultural aspects of painting that are useful to us as we look at painted objects in other cultures and times:

- There is the aesthetic sense of a culture: What is seen as beautiful, what as ugly, what is legitimate as a subject of painting and what not?

- There is a technology. What are paintings painted on, how is the surface prepared, what pigments are used, what binders stabilize them on the painted surface, what solvents are used? What does the painter paint with, how does the painter clean up after himself.

- There is a craft. What must a painter be able to do well to be regarded as a skillful painter in his culture and in his role in that culture?

- How do painters learn to do what they do. How is the training and education of painters institutionalized.

- There are economic concerns. Are inputs and outputs of painting processed through markets, and if so, how do those markets work. If they are not markets, how does the painter get input and place his outputs, and how are these processes institutionalized. How do painters get the resources to meet their needs for food and shelter?

- There are political concerns. How do key institutions related to painting, how do they work, and who are the people who lead them?

If we wish to understand painting in our own and other cultures, these perspective seem important. So to, it seems important to try to understand what a painter is seeking to do, for that sets one standard for the evaluation of the painter's work. When Giotto painted his murals in the Church of San Francesco, in Assisi, he must have been trying to produce works that would help visitors to the church to learn stories about the religion of St. Francis and to strengthen their faith in that religion. I would suggest that we Americans today give more importance to the fact that his work helped spark the Italian Renaissance than he himself would have done. How well did he teach? How well did he inspire the faithful? How well did he exercise the skill of the painter? How well did he inspire later artists? Answering all these questions would be likely to deepen one's appreciation of his work.

These ideas suggest that the social scientists have a great deal to offer to help us understand art. If we understand better what painters were trying to do, how painting comes about, how society institutionalizes different aspects of making paintings, and what limitations are thus imposed on the painted surface, we better understand what we are looking at and how is might be perceived.

There is also a different way to use our cultural concept of art -- a more philosophical way to benefit from the insights of other cultures. Japanese widely share wabi-sabi, which is (in part) an aesthetic valuing nature, impermanence, and imperfection. While this aesthetic influences Japanese art, it also has deep relevance to Zen Buddhism. Perhaps through a study of Japanese art and wabi-sabi one might find insights into how some Japanese understand themselves, the world, and their place in the world. And perhaps we would learn something about ourselves in the process.

So too, the designs of Australian Aboriginal cave drawings with their abstractions from nature are aspects of that peoples Dreamtime mythology. Perhaps looking at and studying those paintings will give some intuition about an alternative way of understanding mankind and the world.

I only wish I could follow this advise of my own more fully!

These ideas suggest that the social scientists have a great deal to offer to help us understand art. If we understand better what painters were trying to do, how painting comes about, how society institutionalizes different aspects of making paintings, and what limitations are thus imposed on the painted surface, we better understand what we are looking at and how is might be perceived.

There is also a different way to use our cultural concept of art -- a more philosophical way to benefit from the insights of other cultures. Japanese widely share wabi-sabi, which is (in part) an aesthetic valuing nature, impermanence, and imperfection. While this aesthetic influences Japanese art, it also has deep relevance to Zen Buddhism. Perhaps through a study of Japanese art and wabi-sabi one might find insights into how some Japanese understand themselves, the world, and their place in the world. And perhaps we would learn something about ourselves in the process.

So too, the designs of Australian Aboriginal cave drawings with their abstractions from nature are aspects of that peoples Dreamtime mythology. Perhaps looking at and studying those paintings will give some intuition about an alternative way of understanding mankind and the world.

I only wish I could follow this advise of my own more fully!

No comments:

Post a Comment