- the rise of a family to power in Oman and Omani society at the beginning of the 19th century,

- the transfer of the Omani Sultanate to Zanzibar,

- the 19th century culture on the island of Zanzibar,

- the slave trade from East Africa,

- the explorations of Burton and Speke, as well as Dr. Livingston and Henry Stanley,

- the Arab-Swahili rule of what would become Tanganyika,

- Tippu Tip

- the scramble for African colonies by the European powers (especially as it affected Zanzibar and Tanganyika, and

- especially the life of a Muslim princess from Zanzibar who converted to Christianity, married a German businessman, moved to Germany, was soon widowed with three small children, who spent the rest of her life as an expatriate seeking support from her ruling relatives in Zanzibar.

|

| Source |

Oman

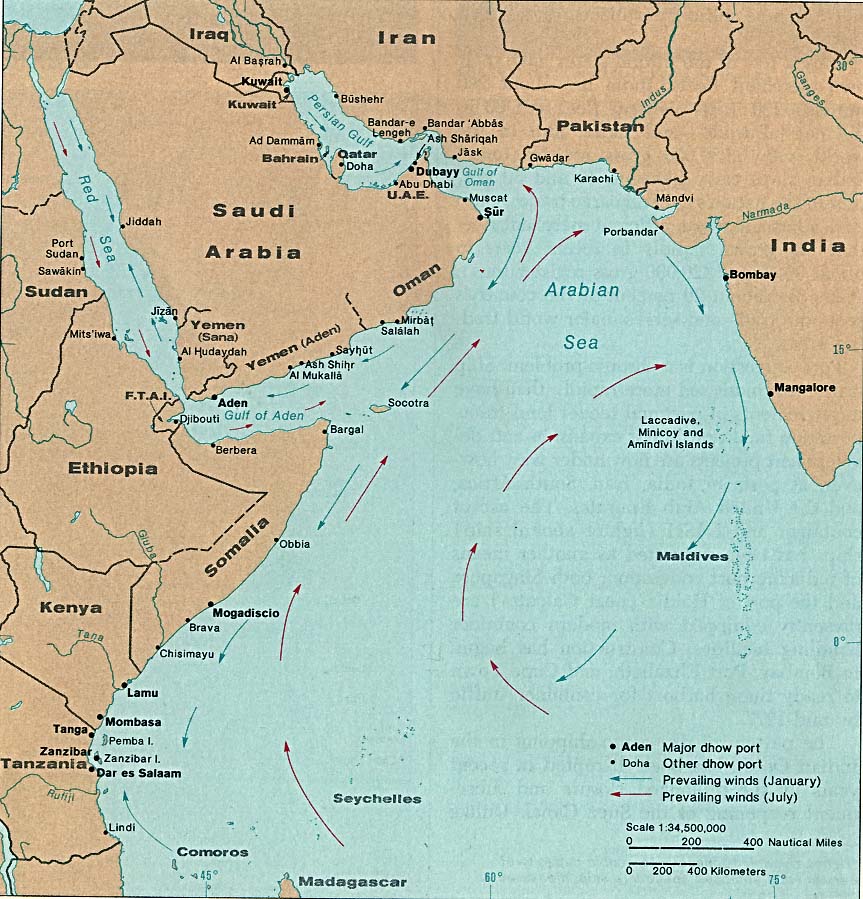

Oman was in a "catbird seat" in 18th century commerce, receiving ships from India, the north shore of the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, the east coast of Africa and its neighboring islands. People from many lands mixed in the markets of its cities, buying and selling the products of many lands. It was also a market for slaves brought primarily from Africa. The country had a sect of Islam that was more tolerant than many others. The ruling Sultan gained great wealth from the custom fees charged on those goods. His household, with several wives, many concubines, many children, and slaves was very elaborate.

On the other hand, politics was literally murderous. Brothers sought to overthrow brothers; tribes formed shifting alliances; Persians threatened and sometimes conquered Oman; Wahabi Sunnis from the Arabian peninsula conducted a jihad against Oman.

The book provides a view of the culture of the country which I certainly did not know and I suspect few readers will know -- but a culture of considerable color and vibrancy.

Zanzibar

Zanzibar was a multi-ethnic society in the 19th century, ruled by Arabs from Oman, with a significant population of Swahilis from coastal Africa, a native population, merchants from India, as well as some Europeans and even Americans. Author Bird focuses primarily on the culture of the ruling Arabs, but gives a flavor of what was an extremely exotic place.

The economy was for much of the century fueled by clove plantations, which were greatly expanded once it was discovered that the island was ideal for the growth of cloves; many clove plantations were dependent on slave labor, providing luxurious standards of living for their owners; late in the century, a storm decimated the trees leading to bankruptcy for many of the plantation owners.

The Arabs and Swahili of Zanzibar also dominated the nearby African mainland, and thus could control the trade in slaves and ivory. With cloves, slaves and ivory to export, Zanzibar could also import goods, including luxury goods for its relatively small affluent population.

The Slave Trade

The British and French slave trade was primarily from West Africa to North America, and that is the one we in the USA are most familiar with. Before Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama pioneered the route around the southern tip of Africa and to India, there was a slave trade from East Africa to Islamic lands. Even when these routes opened, the slaves from what would become Tanganyika were used as bearers for expeditions to and from the interior, for coastal plantations and plantations on the islands, and for sale via Indian Ocean routes.

Author Bird stresses that the treatment of slaves in Muslim culture was different and less severe than in Christian cultures. Indeed, slaves were sometimes armed to serve as bodyguards for their owners. Bird describes different roles for slaves, from concubines, to castrated male household servants in polygamous households, to plantation laborers.

Portuguese slavers, having been effectively barred from West Africa, preyed on the peoples of what became Mozambique; the export was primarily to Brazil.

The capture and transport of slaves was extremely brutal. European explorers described regions laid waste by slave raids. Captives died in great numbers while being marched to the coast. Young boys chosen for castration often died as a result of the procedure.

The abolition of the slave trade is presented in the book as largely the result of British efforts. Dr. Livingston was a strong abolitionist, and his reports back to England stimulated renewed concern in a people that had become complacent. British warships were dispatched to stop slave ships; British diplomats negotiated treaties obliging the Sultan of Zanzibar to make slavery illegal. By stops and starts, the British succeeded and the slave trade was ended, and finally slavery was abolished late in the 19th century.

The Explorers from Outside Africa

Richard Burton and John Speke were famous explorers of East Africa; Speke has a claim to have discovered the source of the White Nile in Lake Victoria. Author Bird devotes a chapter to their adventures and accomplishments as explorers, as well as their difficulties with each other.

"Dr. Livingston I presume." is surely the most famous quotation from East African history, and the book describes the incredible perseverance and tenacity of medical missionary and explorer David Livingstone, and the journey of Henry Stanley to find and rescue Livingstone -- leading Stanley to ask the famous question. Stanley was an intrepid and courageous explorer, a shameless self promoter, and an agent of King Leopold in the pitiless exploitation of the Congo (see my post on King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa by Adam Hochschild).

The Sultans

Much of the book focuses on Seyyid Said, the Sultan who moved his seat of government from Oman to Zanzibar, and two of the four of his sons who succeeded him as rulers of Zanzibar. (He also had two sons who succeeded him as Sultans of Muscat and Oman, who are not subjects of the book.) It is hard to fully appreciate the magnitude of the area ruled by Seyyid Said, but it seems to have included Oman, Zanzibar and Pemba islands, a coastal strip of East Africa, and at its peak, a large area of East Africa. In terms of the land area at least nominally under his control in the 19th century, he ruled an area larger than most European countries. He was also very wealthy.

Seyyid had several wives and many concubines, as well as 36 children. His household is a major topic of the book. Seyyid Mujid and Seyyid Barghash are the Sultans of Zanzibar most discussed in the book.

Arab Swahili Rule in East Africa

East Africa was exploited for slaves, ivory and gold. Safaris were organized into the interior to obtain these goods, leading to the establishment of towns occupied by traders, and eventually to conquest of large territories where tribal chiefs paid tribute to the "foreign" rulers in these goods.

The Swahili are described as an African coastal tribe who were converted to Islam very early. They eventually formed a close alliance with the Arabs resident in Zanzibar and East Africa. Author Bird notes that Arab men married into the Swahili although Swahili men did not marry Arab women. KiSwahili, the language of the Swahili with many borrowings from Arabic, became a common language for the region. The Arabs and Swahili apparently became partners in the commercial and eventually the political exploitation of the region.

Tippu Tip

The book contains a chapter devoted to Hamad bin Muḥammad bin Jumah bin Rajab bin Muḥammad bin Sa‘īd al-Murghabī better known for obvious reasons as Tippu Tip. Truly an amazing man.

Of mixed Arab and Swahili ancestry, he began as a trader but took the opportunity to acquire land by conquest. Eventually he ruled the Eastern Congo for himself and for the Sultan of Zanzibar, Bargash bin Said el Busaidi.

After adventurous years in East Africa, including helping explorers including Henry Stanley, Tippu Tip returned to Zanzibar, bringing with him 70,000 pounds of ivory and thousands of slaves.

He became even richer in his subsequent life in Zanzibar, eventually owning many plantations and many thousands of slaves. He even wrote his autobiography!

The Scramble for Africa

The book looks back at East Africa and the Arabian peninsula before Europeans managed to sail around the southern tip of Africa, and continues until the end of the 19th century, when Africa was divided among European nations. Consequently the reader understands that the Sultanate of Zanzibar, no matter how rapid its rise and how splendid its court at its peak, is doomed.

While Portuguese, French and even Americans make appearances in Zanzibar and East Africa, the early power is clearly England, with its control of India. English sea power is applied to abolish the slave trade, and treaty agreements with Britain strengthen the Omani and Zanzibar Sultanates.

Bird describes the British and Germans, essentially without local input, deciding between themselves that Tanganyika would become a German colony and Kenya would become a British Colony. Later, in 1890, Germany and Britain made a territorial trade, giving the British control over Zanzibar. That spelled the end of power for the Sultans of Zanzibar.

Princess Seyyida Salme - Emily Ruete

|

| Princess Salme |

The heroine of the book is Princess Salme. She was one of the daughters of Sultan Seyyid Said, brought up in great luxury in his palaces, in a society formed largely by the Sultan's wives and children and their servants. As an adult she was given plantations and slaves. However, on the death of her father, she was caught in the struggle for power between her brothers.

She did the unthinkable for a sequestered Muslim princess, and fell in love with a Christian -- a German trader living in Stone Town, the capital of Zanzibar named Rudolph Heinrich Ruete. She was smuggled out of Zanzibar, and after some months he joined her. Salme was converted to Christianity, and married to Ruete (taking the name of Emily) in 1867. There were three children born of the marriage, but her husband died in 1870. Emily Ruete was left a widow with three small children in Hamburg, an environment in which she was unprepared; moreover, author Bird indicates that she received little or no support from her husband's family, and was dropped by the friends that she and her husband had shared in Germany.

|

| Emily Ruete |

On the other hand, she had brought her personal jewelry with her to Germany, and it was sufficiently large and valuable a collection that she and her husband had difficulty convincing German customs officials that it was for personal rather than professional use. Moreover, she was exceptionally well educated for the daughter of a Sultan, was very intelligent, and had already achieved some fluency in German. As a Princess she could draw on German and English aristocrats for some forms of assistance.

Princess Salme spent almost all the rest of her life seeking an inheritance or at least a supporting pension from her family in Zanzibar. In her efforts she was helped by many aristocrats, and even apparently by Queen Victoria. Still, English and German diplomats were reluctant to champion her cause. Her brothers, the Sultans, apparently saw her conversion to Christianity and her elopement as unforgivable.

Emily Ruete wrote and published her biography, the first African woman to do so. The book and her letters apparently were a major source used by author Bird in writing The Sultan's Shadow.

Final Comment

I have been looking for good books on African history for some time, and this fit the bill. I had no idea of the history of Oman, Zanzibar and East Africa that I learned from this book. As the description above suggests, the book is unusual in that it treats a large number of relatively discrete topics. However, the author intertwines them in an convincing web. It is largely cultural history, and the cultures it depicts, especially those of royal households in Oman and Zimbabwe, fascinated me. The author appears to be a professional travel writer rather than a professional historian, perhaps accounting for her ability to tell a great story. In short, I loved the book!

No comments:

Post a Comment