I just read A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal by Ben Macintyre. I previously posted some background for reading the book. There is a most interesting Afterword by John le Carré.

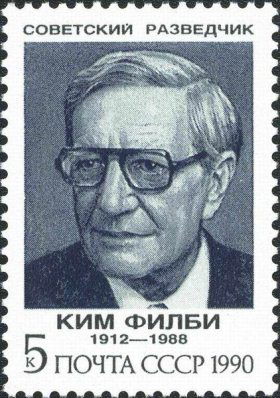

Kim Philby was perhaps the most famous double agent of the 20th century, working for Britain's MI6 while also a spy for the USSR. The book seeks to describe Philby and how he could successfully lead such a double life. It also seeks to understand MI6, the British counterpart to the CIA, and how Philby could survive successfully for so long without being caught out by British and/or American intelligence.

Philby was recruited by the Soviets in the early 1930s. He was one of the "Robber Barons", a group of young Englishmen recruited for British Intelligence at the beginning of World War 2. He was a rising star in MI6 when he was implicated in the successful escape to Moscow in 1951 of Burgess and MacLean, two Soviet spies who were British diplomats. His role in the "Cambridge Spy Ring" was not proven at that time, but he was forced to resign from MI6 in 1951 (apparently he also became inactive as a Soviet spy at that time). In 1956 he was reemployed by MI6 as an agent in Beirut, under cover of a foreign correspondent (and apparently was reactivated as a Soviet spy). By 1962 new evidence had developed further implicating Philby as a Soviet spy; he was interrogated and made a partial confession. He then fled to Moscow where he was well treated as a valued long term agent for the Soviets.

Who Was Kim Philby?

Part of Macintyre's answer is that Philby was a charter member of the English establishment, wealth, son of a distinguished and well connected father, educated at Westminster School (one of the posh public schools) and Cambridge University. He was tall and thin, handsome and apparently charming; he dressed well. He was sufficiently competent as a journalist to become a credible foreign correspondent in the Spanish Civil War, with the British Expeditionary Force before Dunkirk, later in France until its surrender to the Germans, and much later for The Observer and The Economist in the Middle East. He was sufficiently competent in his work for British intelligence to rise quickly in MI6, and was an exceptionally important agent for the USSR. He also drank to excess, sometimes disrupting dinner parties with drunken remarks and apparently later in life often drinking to the point of passing out.

Philby married a Communist woman in 1934. After they separated, he began began a long term relationship with another woman, one who was mentally ill, and they had five children together; they were not married until after the war, when he finally divorced his first wife. Later, when he had moved to Beirut, he had an affair with a colleague's wife; when his second wife died and his lover divorced her husband they were married -- his third marriage. After he defected to Russia, although his wife had joined him there, he had an affair with MacLean's wife. His third wife divorced him, and MacLean's wife left him. Finally he married a much younger woman and lived successfully with her in Moscow. He seems to have retained good relations with his children.

Author Macintyre also suggests that Philby had an exceptional capacity to get others to like and trust him, at least others who shared his social background. It seems credible that he in turn believed that many of the people he was in fact betraying were truly his friends.

How Could He So Fool British and American Intelligence Agencies?

There apparently was no real background check before he was recruited for the British government early in World War 2. His father was well known, he was of the right class, and it appeared that the people responsible for his entry could not conceive of his being a Soviet spy. Had they considered his early socialist leanings and his activities in the Great Depression, his marriage to a communist, and his work to extract communists from Nazi Germany before the war, they might have wondered. Indeed, he had also been associated with Nazi related organizations, and Nazi Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop had provided Philby with a letter of recommendation to Franco's Spanish government -- which might have made them wonder if he would be a Nazi double agent.

Clearly the British were desperately trying to expand the size and activities of their intelligence agencies during the war, adding both deception and sabotage to their charter. The failure to uncover Philby's past might have been simply due to a decision to put limited resources to other uses. The U.S. OSS was brand new and was seeking to learn the craft of intelligence from the British. OSS operatives were in no position to challenge Philby during the war.

After the war, Philby's history (described above), his drinking, and perhaps womanizing might have raised concerns. Certainly his association with Burgess (who lived in Philby's house in Washington) and MacLean did. The FBI and MI5 (roughly the British equivalent to the FBI) were very much concerned. However, MI6 was unable to make a convincing case against him in 1951, nor was the CIA. Macintyre suggests that the FBI and MI5 were staffed by more middle class officers, and that they did not have the upper class, club like atmosphere he feels characterized MI6 at the time, especially among the "Robber Barons" who had served through the war together and formed strong interpersonal bonds.

Macintyre suggests part of the explanation was the inability of Nicholas Elliot of MI6 and James Angleton of the CIA to believe Philby was a communist nor a Soviet spy. Both were personal friends of Philby; Elliot was English of the same social class and Angleton was educated in England and is depicted as an Anglophile. Both are depicted as having difficulty in believing someone apparently so like themselves could have such fundamentally different beliefs. or could behave in a way that they found so unimaginable for "one of themselves".

Macintyre suggests that in 1956 Elliot, then "a grandee" of MI6, was almost solely responsible for bringing Philby back into that organization. Perhaps the lack of checks and balances in the hiring process within MI6 was partly responsible, or perhaps the lack of need for the foreign intelligence services to clear recruitment of agents abroad with the domestic intelligence services.

Problems With Any Such Book

It is always difficult to reconstruct the past, and Ben Macintyre is a journalist rather than a professional historian. He perhaps lacks some of the tools of the professional, but even the most consummate historian would have difficulty with this topic. Angleton destroyed records of his interactions with Philby; MI6 will not release its Philby files; the Soviet files that have been released by the Russian Federation may not be fully trustworthy. The secrecy of the intelligence services suggests that there would be few contemporary useful public records to shed light on Philby and his career.

Macintyre was necessarily selective in what he wrote. As we look at succeeding generations of writers dealing with the same moment of history, we know that they choose different items to feature in their texts, supporting different points of interpretation and different purposes for their works.

Sometimes, in this book, Macintyre seeks to imagine what was going on in someone's mind that he should have behaved as he did at a given time; we think with our brains, and are not always fully aware of why the brain comes to the decisions it does. Even if Philby, Elliot, Angleton and others in the book were so aware at the time, they might later not recall correctly. Like all people, these people can not be assumed to be trying to tell the exact, unvarnished truth, but unlike most people, these are professional intelligence officers trained in deception; their memoirs are not to be fully believed. The author picks and chooses which stories to credit, which to reject, which to accept as modified, and he may be wrong.

What I Thought of the Book

Think of the times and places of Philby's life: a child in India during the British Raj, a boy in one of the great public schools of England between the wars, a student at Cambridge during the Depression, in love with a Jewish communist in Vienna in the 1930s helping political refugees escape from burgeoning Nazi persecution, infiltrating Nazi organizations in Europe before the war, covering the Spanish Civil war as a foreign correspondent, covering the British Expeditionary Forces in France before Dunkirk, covering France in the last days before surrender to Germany, running spies in Spain and Portugal during World War II, playing the double game in Istanbul in the late 1940s, spying in the heady social atmosphere of diplomatic Washington (1949-51), living in Beirut and covering the Middle East as a double agent and foreign correspondent in the late 50s and early 60s, and even as an honored former spy in Moscow through the later years of the Soviet Union. Author Macintyre was not trying to portray these fascinating places, times and activities, but I could not help trying to imagine them.

It was interesting to read about what Philby was known to have done; indeed it is interesting to know that a person actually lived such a life and did such things. However, I doubt that it is possible to really understand him and to really understand why he did what he did. Was he a committed ideologue, a man who could completely compartmentalize his life and not worry about the ways in which one part would destroy another, an adrenalin junkie, a sociopath, some combination of those, or something different again? I don't know, but I don't expect that to be knowable and am willing to live without that knowledge.

Why was Philby not caught? I tend to assume incompetence or an overloaded bureaucracy letting something important "slip by". Perhaps Macintyre is right that the culture of Philby's stratus of English society (that was running MI6) was responsible for his success. Macintyre also suggests that the Robber Baron's who fought the spy war for Britain and the USA during the war had a comradery that required them to "guard each other's backs"; it seems intuitive that such a loyalty might have existed and would have made it very difficult for Elliot and Angleton to believe in Philby's treachery or to vigorously prosecute him. Whatever the reason that he got away with spying for the Soviets for so long, I suspect that the conditions in the intelligence agencies are much different now. (Intelligence now seems much more a matter of technology, agencies much more established bureaucracies with a far more complex structure, staffed by professionals with a wide variety of skills and backgrounds, with much more developed systems for vetting staff and guarding against penetration.)

The bottom line is that A Spy Among Friends is an interesting book, a page turner, that made me wonder and think about espionage, the diversity of human experience, and interesting times and places! I enjoyed the book!

1 comment:

Perhaps the English class system is still more alive than I had realized, at least in terms of private schools and elite universities.

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/nov/30/private-schools-game-elite-universities-privilege

Post a Comment