There is an interesting column in The Economist magazine this week, dealing with the ability of countries to deal with another financial crisis if one should arise in the near future.

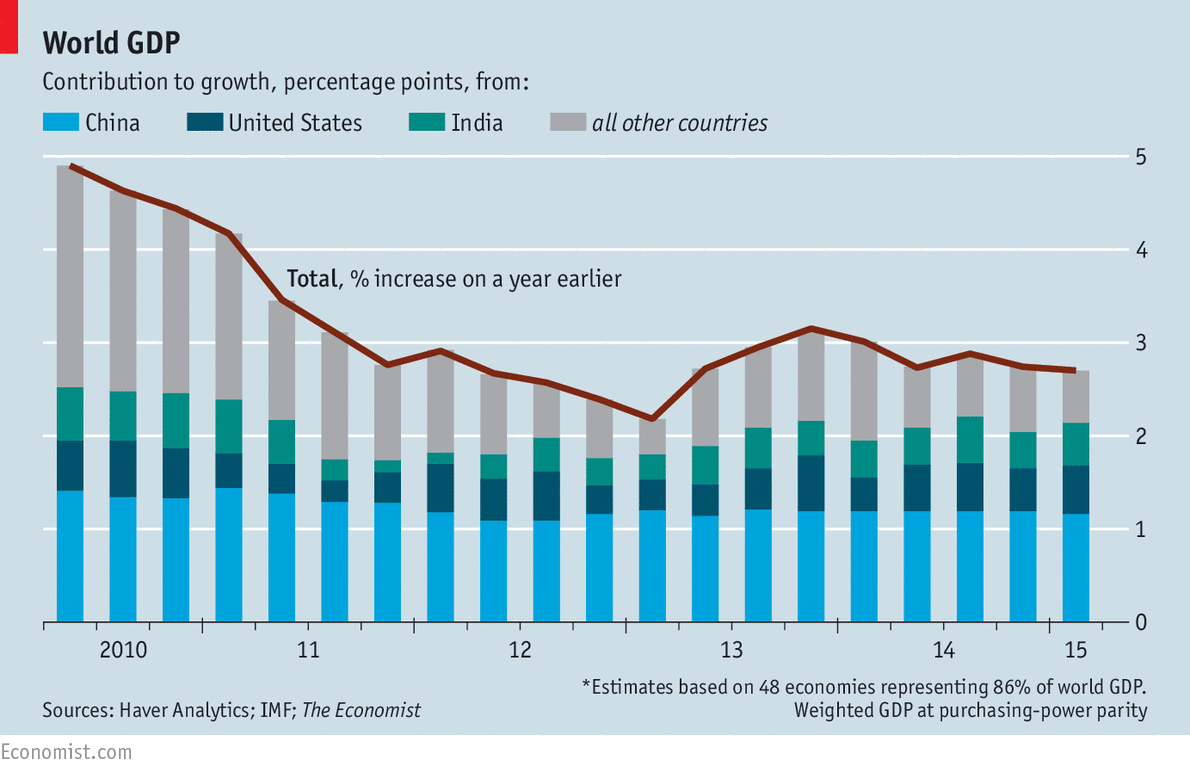

An article last week in the same magazine pointed out that economic growth had been pretty good in China, the United States and India in the past few years, but remains quite low in the rest of the world. While these three countries together represent a considerable portion of the world's people and GDP, the lack of growth in other economies troubles me.

The euro area’s slow recovery has continued; the 19-country bloc experienced 1.1% year-on-year growth in the first quarter of 2015 compared with 0.9% in the previous quarter. Leaving aside China and India, emerging markets struggled in the first quarter. They contributed less than 13% of global growth, the smallest proportion since late 2009.

Governments seek to support the economy in crises by various methods.

- Central banks lower interest rates but: "Central banks’ benchmark interest rates hover above zero......they will probably remain close to that level for some time to come. Futures prices suggest that the Fed’s main rate will be around 2% in early 2018. Traders expect the Bank of England’s to be about 1.5%, and those in Europe and Japan to remain stuck near zero."

- In this Great Recession, central banks printed money to buy bonds in an effort to provide additional stimulus—a policy known as quantitative easing; we still have to see the effect of liquidating the bonds bought with created money, and it may be ugly. "(In Japan) the central bank now owns almost 30% of the public debt."

- Governments seek to increase spending to stimulate the economy; since tax income goes down in recessions, governments borrow to do so. But many governments are already running budget deficits that are a significant fraction of the GDP. Some governments have already borrowed so much (relative to their country's GDP) that they will not easily borrow more. "The mountain of public debt accumulated since 2007 adds a further constraint. Debt as a share of GDP is, on average, 50% higher than it was before the crisis."

I assume that a vigorous recovery would have helped. Had the GDP increased rapidly, the debt to GDP ratios would have correspondingly decreased. Central banks would have increased interest rates, and would have reduced the rate of quantitative easing. Tax revenues would have improved, There would have been more "wiggle room". But many governments chose austerity policies designed to reduce debt (while accepting relatively lower rates of economic growth).

We will no doubt see what we will see!

No comments:

Post a Comment